Products You May Like

On Monday, the day after Liverpool‘s 5-0 destruction of Manchester United at Old Trafford, every major publication (including this one) ran pieces on the match as either a referendum on the mediocrity that United have become, as an end-of-days moment for Ole Gunnar Solskjaer’s tenure as United manager, or both. A piece in The Independent, however, stood out for one particular reason. Amid talk of the need for a “cultural reset” at the club, Miguel Delaney noted, “Key decision-makers at the club willingly say they never wanted to go down the Manchester City or Liverpool route of having a defined style of coach, because that means you can’t be adaptable.”

Imagine watching Liverpool-United on Sunday, seeing Liverpool cut with ease through the weakest, most unorganized high press they’ve seen all season. Imagine watching Mohamed Salah post the easiest hat-trick of his life and his team carving through United with ease, pouncing on mistakes and romping to five goals in 48 minutes, seemingly without ever having to shift past about fourth gear. Imagine seeing all that and thinking, “Meh, too inflexible.” It boggles the mind.

– ESPN+ viewers guide: LaLiga, Bundesliga, MLS, FA Cup, more

– Stream ESPN FC Daily on ESPN+ (U.S. only)

– Don’t have ESPN? Get instant access

Whether Liverpool is a particularly “adaptable” club at the moment or isn’t, one thing is certain: they’re playing really, really well. They are pressuring the ball as much as they ever have, they are attacking with a bit more intensity and verticality, and Salah, long one of the world’s best players, is producing at an otherworldly clip.

Like plenty of clubs, Liverpool would probably like to forget the 2020-21 season altogether. The Reds pulled an incredible salvage job late in the season, taking 26 points from their last 10 matches to secure a top-four finish (and Champions League bid) that seemed terribly unlikely as late as March. But everything that brought them to that unlikely place — centre-back injuries, more centre-back injuries, midfield injuries, early-season COVID-19 diagnoses, a run of six losses in seven matches in the early months of 2021 — was a source of massive frustration and made Liverpool a very difficult team to preview this summer.

They barely made any offseason moves, either, primarily trusting that players like defenders Virgil Van Dijk, Joel Matip and Joe Gomez and midfielder Jordan Henderson would return to previous form after injury; they spent their entire transfer budget on a young centre-back (Ibrahima Konate) who’s barely played thus far, and they brought in no midfielders to replace the departed Georginio Wijnaldum (PSG) and Xherdan Shaqiri (Lyon).

The results thus far make a lot more sense if you indeed pretend 2020-21 didn’t exist.

-

Liverpool in 2018-19 (Premier League only): 2.55 points per game, 2.3 goals per game, 0.6 goals allowed, +1.2 xG differential per game

-

Liverpool in 2019-20: 2.61 PPG, 2.2 goals, 0.9 allowed, +0.9 xGD

-

Liverpool in 2021-22: 2.33 PPG, 3.0 goals, 0.7 allowed, +1.8 xGD

Seems like a high-continuity team that continues to gel and find higher levels of play, right?

Heading into the weekend, Liverpool have the best xGD in the Premier League, rank first in both goals scored and xG and rank third in both goals and xG allowed. They are just one point behind first-place Chelsea, and you could say they’re unlucky to be even there — they out-shot Chelsea 24-6 in a 1-1 draw in August (xG: Liverpool 3.4, Chelsea 0.7) and generated more xG value than Manchester City in a 2-2 draw in early October as well.

Liverpool have still battled some injury issues — only one midfielder (Henderson) has recorded more than 65% of available minutes in all competitions this season, with six others between 23%-65% — but it hasn’t mattered in the least. They’re unbeaten in league play, they’ve already all but qualified for the Champions League knockout stages with three wins in three matches, and they haven’t actually lost a competitive match since 1-0 to Fulham on Mar. 7.

How have they done this, and is this the best they’ve been under Jurgen Klopp?

The defense has improved as expected

The 2020-21 season did, in fact, exist. Chelsea has the Champions League trophy to prove it. Liverpool indeed lost to Fulham (and a bunch of other teams) and found itself in eighth place in the Premier League in mid-March.

As you might expect from a team that lost Van Dijk, Matip and Gomez (and then Henderson as well) to long-term injuries, the Reds found themselves unable to remain organized in transition defense. They allowed the second-fewest shots per possession in the Premier League (0.90), but they also allowed 0.15 xG per shot — worst in the Premier League and third-worst in all of Europe’s Big 5 leagues, ahead of only Italy‘s nearly relegated Spezia and Germany‘s all-or-nothing Hoffenheim.

In part because of these transition issues, their close-games fortune vanished, too: In matches decided by 0-1 goals, they went from averaging an unsustainable 2.50 points per game in 2019-20 to 1.43 in 2020-21. They saw a 68-match Premier League unbeaten streak end at Burnley‘s hands in January, then proceeded to lose their next five league matches at home as well.

1:22

Steve Nicol debates whether Ole Gunnar Solskjaer will be sacked after Man United’s 5-0 defeat to Liverpool.

With Van Dijk and Matip healthy and recording most of the minutes, the defense has righted itself as one might have expected. Liverpool ranks second to City in shots allowed per possession (0.11), but they’re back to ninth in xG allowed per shot (0.11) — a solid place for a heavy-possession team to be. For comparison, the 2018-19 Liverpool team, which won the Champions League and finished a narrow second to City in the Premier League (and, honestly, was probably better than the 2019-20 team that won the EPL), allowed 0.08 shots per possession and 0.11 xG per shot. That resulted in a full-season average of 0.6 goals allowed per match.

Considering Van Dijk damn near won the Ballon d’Or in 2019, we knew he was pretty good, and we now have pretty solid statistical evidence of the impact he makes when he’s in the lineup. (We also have evidence of what can happen when you have to shuffle centre-backs almost match to match because of injury: bad things.)

More directness in attack

Statistically, there’s been another interesting change beyond Liverpool’s defensive improvement: they’ve also been a lot more aggressive on the offensive end. Their average of 0.22 shot attempts per possession is a massive increase — they had averaged between 0.15 and 0.16 for each of the last three seasons, which adds up to about six extra shots per match. They’re also averaging 0.14 xG per shot, slightly higher than what the 2018-19 team managed.

Liverpool are ending 47% of their possessions in the attacking third, and they’re averaging both 25.4 meters per possession and 26.3 seconds per possession — both the highest averages of the last four seasons. And this isn’t idle possession either: Their direct speed* is 1.41 (highest of these four seasons), 31% of their passes have been forward (highest), and they’re completing 54% of their long-ball pass attempts (highest). Combine that with a defense that is as aggressive as ever — 9.7 passes allowed per defensive action (second in the Premier League), 9.8 possessions per game started in the attacking third (second), average starting position for a possession 38.4 meters upfield (first) — and Liverpool has had no problem creating dangerous opportunities.

(*StatsPerform defines direct speed as “the number of metres that the ball travels (when measuring directly up-field), divided by the total time of [a given] sequence.” It is a measure of directness. The counter-attacking Burnley currently has a direct speed of 1.87, while the ultra-patient Brighton currently comes in at 0.97. Liverpool is almost directly in the middle.)

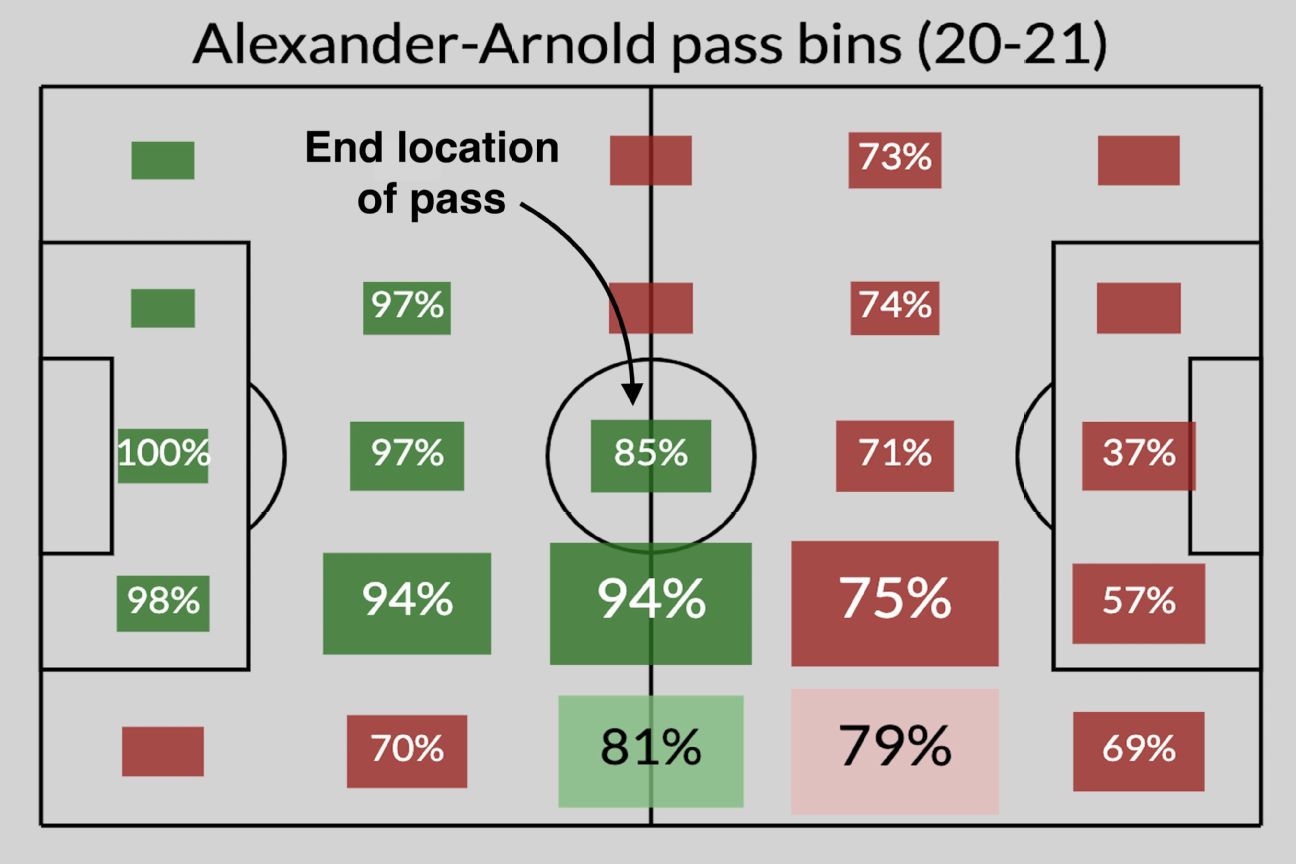

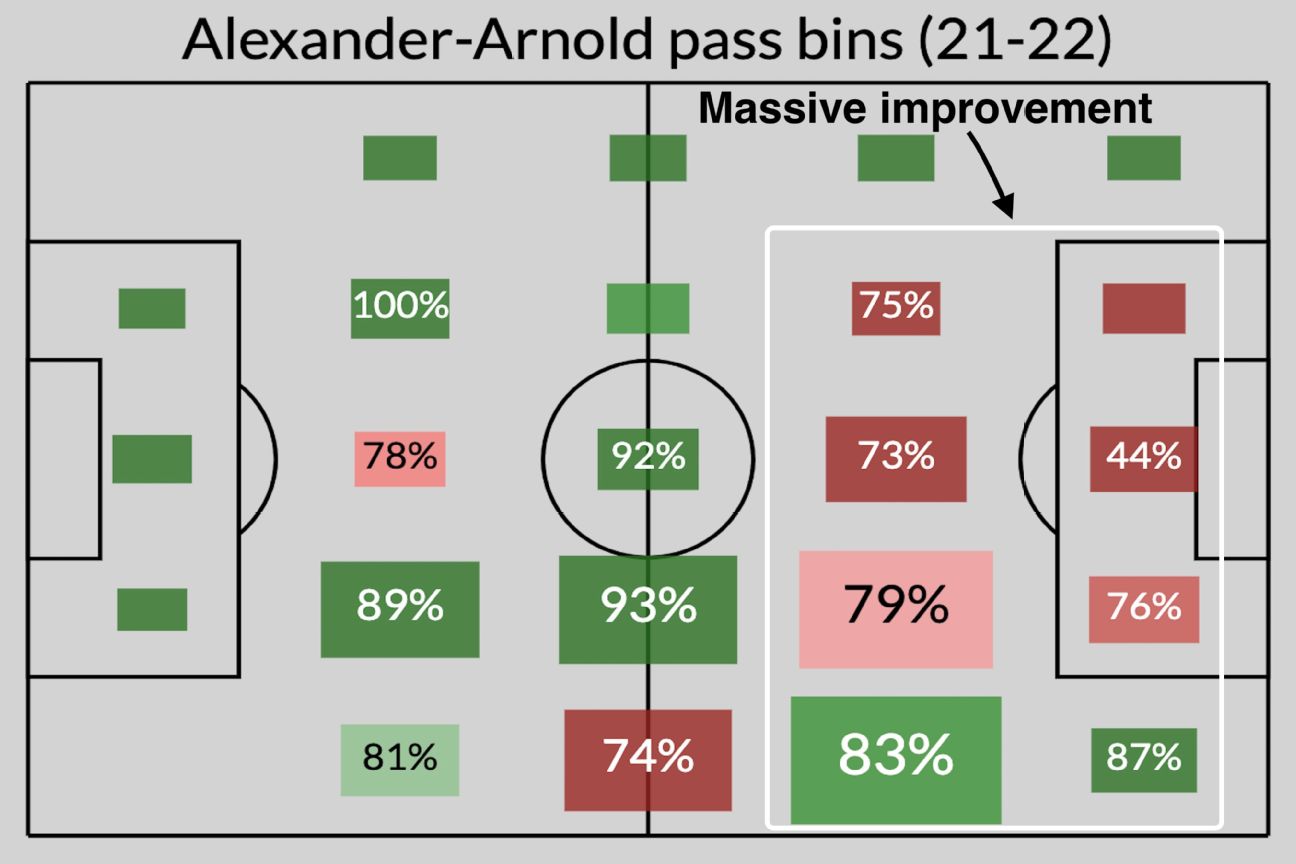

This is an aggressive attack. Left-back Andy Robertson has gone from averaging 0.15 assists and 1.68 chances created (assists + key passes that led to shots) per 90 minutes in all competitions to 0.22 and 2.13, respectively, while right-back Trent Alexander-Arnold has found a higher gear from a creation standpoint. He has improved from 0.21 assists and 2.23 chances created per 90 in all comps last season to 0.35 and 3.23 to date.

Though he’s only played in seven of Liverpool’s nine Premier League matches thus far, Alexander-Arnold is second in the league with 25 chances — ahead of players like Salah (22) and City’s Jack Grealish (21) and behind only Manchester United’s Bruno Fernandes (34).

Alexander-Arnold’s passing has improved across the board in attacking areas.

Source: TruMedia and StatsPerform

In terms of pass volume, Alexander-Arnold is even more involved up the pitch (and less involved in the areas full-backs generally patrol) than last season, in part because that’s where the ball typically is — Liverpool is doing as well as ever at pinning opponents in their half. Plus, he’s got the hottest player in the world as a dance partner out wide.

Super Mo

We can never just talk about the present tense in this sport; everything has to be tied to a future event, be it a transfer, a contract renewal or an eventual loss of form. For instance, Paul Pogba‘s name isn’t “Paul Pogba” at the moment, it’s “Paul Pogba, whose contract expires next summer…”

With Salah, the issue attached to his name is also an expiring contract. Mind you, it doesn’t expire until 2023, but with Liverpool’s squad continuing to age and drift past its theoretical peak — Henderson is 31, Van Dijk, Matip and forward Roberto Firmino are 30, Salah and winger Sadio Mane are 29 — the future doesn’t feel all that far away for Liverpool. The club will have to figure out which aging pieces to keep, and as maybe the best player in the world at the moment, Salah’s status is the first priority.

One assumes the club will give Salah what he wants, or at least most of it. Sure, that will likely result in the club deciding to let other key players’ contracts expire because they can’t keep everyone into their mid-30s. And sure, the number of wide forwards who play at a high level into their 30s is pretty small. But the number of players capable of doing what Salah is doing on the pitch at the moment is even smaller — like, one. (It’s Salah.)

Salah has played in each of Liverpool’s nine Premier League matches and has scored in eight. He’s scored in all three Champions League matches. In all competitions, he’s scored 15 goals and created 27 chances. He is on a Allen Iverson-like run of crossing up defenders and sending them to the ground.

For almost any player on the planet, this would be the best goal of his or her career, but it wasn’t even Salah’s best goal of October. This was.

By comparison, Salah’s hat-trick against Manchester United was downright easy. Either way, he’s on an almost unmatchable run, one perhaps no player can sustain for an entire season.

So what happens when Salah (and Liverpool) cool off?

Despite the one-point deficit to Chelsea in the table, it’s hard not to think of Liverpool as the best team in England right now. Salah’s form will inevitably become a little less superhuman over time, and the Reds’ average of 0.56 set piece goals per match in Premier League play (shared by Arsenal and Chelsea) will almost certainly come down over time as well.

The attack is almost certainly running too hot to maintain, but if they maintain this form for another 4-5 matches before cooling down, they’ll have set themselves up for a long run in both the Premier League and Champions League.

Liverpool’s next five matches:

Brighton and West Ham are fifth and fourth in the Premier League heading into the weekend, Arsenal is smoking hot, and Atletico and Porto are the two other Champions League Group B teams positioning for advancement to the knockout rounds. Get through this batch of matches with minimal dropped points, and they’ll be set up nicely moving forward.

Over time, they can afford to cool off a little bit on the offensive end and still rack up points — every Premier League win has come by multiple goals, after all — but if or when the goals get tamped down a bit, we could see some other issues emerge.

The major issue could end up being midfield depth. Their chemistry has been impressive considering the amount of match-to-match rotation involved in midfield, but at some point the lack of go-to options in big matches could be an issue. Henderson is healthy and playing well, but he’s 31. James Milner has been counted on for over 500 minutes in midfield and at full-back, and he’s 35. Fabinho struggled through injuries for much of last season, and both Thiago and Harvey Elliott are out with injury — Elliott’s will likely keep him until 2022. That they did not replace Wijnaldum and Shakiri with any new acquisitions has not backfired yet, but it’s only one or two more injuries away from becoming an issue.

Still, Liverpool is playing mostly within itself, Salah’s current transcendence aside, and while the Reds didn’t make the expensive acquisitions that Chelsea and City have made in recent transfer windows, they still have the core of a recent Premier League and Champions League champion in place, and they are playing like a team intent on contending. And that makes sense — in a world in which 2020-21 didn’t exist, they never stopped contending.