Products You May Like

To some people, it might seem strange that two of the best goalkeepers in the world — perhaps even the best — are both from Brazil. After all, Alisson of Liverpool and Ederson of Manchester City — No. 1 and No. 4 in the 2019 FC 100 respectively — hail from a country where it has sometimes been felt that Brazil accumulated World Cups in spite of their keepers, not because of them.

The above might be harsh on Gilmar, from the 1958 and ’62 World Cup-winning teams, though Felix from 1970 was certainly nothing special: the Selecao scored 18 goals over six games and conceded seven. It’s true, though, that times have changed.

One of the best keepers from Brazil’s past was Emerson Leao, first choice in 1974 and ’78, but bizarrely overlooked for the 1982 tournament. At the start of the century, Leao had a brief spell (11 games) in charge of the national team. With characteristic frankness, he pointed out that he might have been good as a player, but the keepers he had to choose from in 2000 were much better. The likes of Marcos, Julio Cesar, Dida and Rogerio Ceni were way ahead of the old guard.

This is no coincidence; rather, it’s the outcome of a process.

Brazil have long taken physical training seriously. They had specialists working with the national team as far back as the 1958 World Cup; by contrast, the standard practices in England for decades after that involved a few laps round the pitch followed by a visit to the golf course. In the post-mortem following Brazil’s disappointment in the 1966 World Cup, the fact that the team’s physical trainer came from a judo background was singled out as a mistake. For Mexico 1970, they even followed a training programme designed by NASA, the U.S. space agency, to cope with the altitude in Mexico.

It was only a matter of time before specialist attention was given to the goalkeeper, too. After all, it’s a position with special needs and requirements and it benefited from a wider trend. After defeat to the Dutch in the 1974 World Cup, Brazilian football focused on the supposed need for more physicality. The athletic development of the game, it was thought, meant that Brazil would have to equal the physical power of the northern European nations in order for their superior technique to tip the balance. There might have been flaws in this thinking in terms of outfield players, but the bigger, stronger, fitter approach clearly helped produce better goalkeepers.

We can also pinpoint the “before and after” moment — or, rather, a “before and after” player.

Claudio Taffarel played three World Cups for Brazil (1990, ’94 and ’98) with scarcely a blemish. (Twelve goals conceded in 18 games, winning one tournament and finishing second in another.) He also proved his worth in European club football and his second move to the continent, joining Galatasaray in 1998, opened the door for Brazilian keepers to cross the Atlantic. He also played a crucial role in the development of Alisson.

Taffarel is the goalkeeping coach for the Brazilian national team. Back in 2015, the position had become a problem. A fine generation had aged out and a clear candidate hadn’t emerged to replace them. Brazil were beaten in the opening round of the 2018 World Cup qualifiers. For the next round, just a few days later, they made a bold change. Out went Jefferson, experienced but unconvincing. In came Alisson, who’d just turned 23 and was untested.

It had been barely a year since Alisson replaced the veteran Dida as keeper for Internacional, in the south of Brazil, but Taffarel had been keeping tabs on him. It is Taffarel’s old club and he saw aspects of himself in the youngster. Much of Taffarel’s success had been based on a sound temperament — a realisation, as he explained to me many years ago, of the necessity to not get too carried away with good or bad moments. He spotted the same even keel in Alisson.

From a goalkeeping family — his father played amateur football and he came through the ranks at Inter following his older brother, Muriel, who is currently with Fluminense — Alisson showed impressive maturity. He could concentrate, he made few mistakes and he boasted the ability to put a mistake behind him. He was a lot like Taffarel, only better built for the position: taller, bulkier and more commanding. So Taffarel made the recommendation and Brazil had a new keeper.

The decision to parachute Alisson into the Brazil starting lineup met was with widespread criticism, not least from within the goalkeeping community. Some thought it was premature, yet it proved to be an excellent move. Alisson showed the same strength of character that immediately impressed on his move to Anfield. He stepped into the side aware of his responsibility, which inspired rather than overawed. Brazil kept faith with him even when he spent his first season with Roma on the bench, and he’s never let them down. The position was undoubtedly his from the night when they hosted Argentina in a World Cup qualifier back in 2016: Alisson made a flying save to stop Argentina taking the lead, a clear turning point on the way to a 3-0 victory.

Alisson is Brazil’s first choice but he’s being pushed every step of the way by the man down the road at Manchester City.

If the career of Alisson intersects with Taffarel and Dida, then Rogerio Ceni and Julio Cesar have had an influence on Ederson. Ceni spent more than two decades with Sao Paulo, where he distinguished himself not only for the shots he saved but also for those he sent flying in the back of the opposition’s net. A free-kick specialist, Rogerio Ceni scored more goals than any other keeper in the history of the game and this clearly had an impact on the club’s youth development work. Ederson had originally been an outfield player, but when he joined Sao Paulo at the age of 13, he soon became a keeper with a booming boot. “We tested him and were surprised by his technical quality and by how quickly he picked up the basics of the position,” says Luizinho, one of his early coaches.

At the age of 15, Ederson surprisingly moved on. It seems likely that the Sao Paulo youth coaches, anxious for quick results, gave more chances to others who had grown taller more quickly. It was their loss. Ederson had a chance to go to Portugal and join Benfica, where he developed, turned professional and gained experience on loan to minor clubs before eventually replacing Julio Cesar in the first team. It was his displays there in the Champions League, not to mention his big-money move to City in the summer of 2017, that brought him to the attention of the Brazilian public.

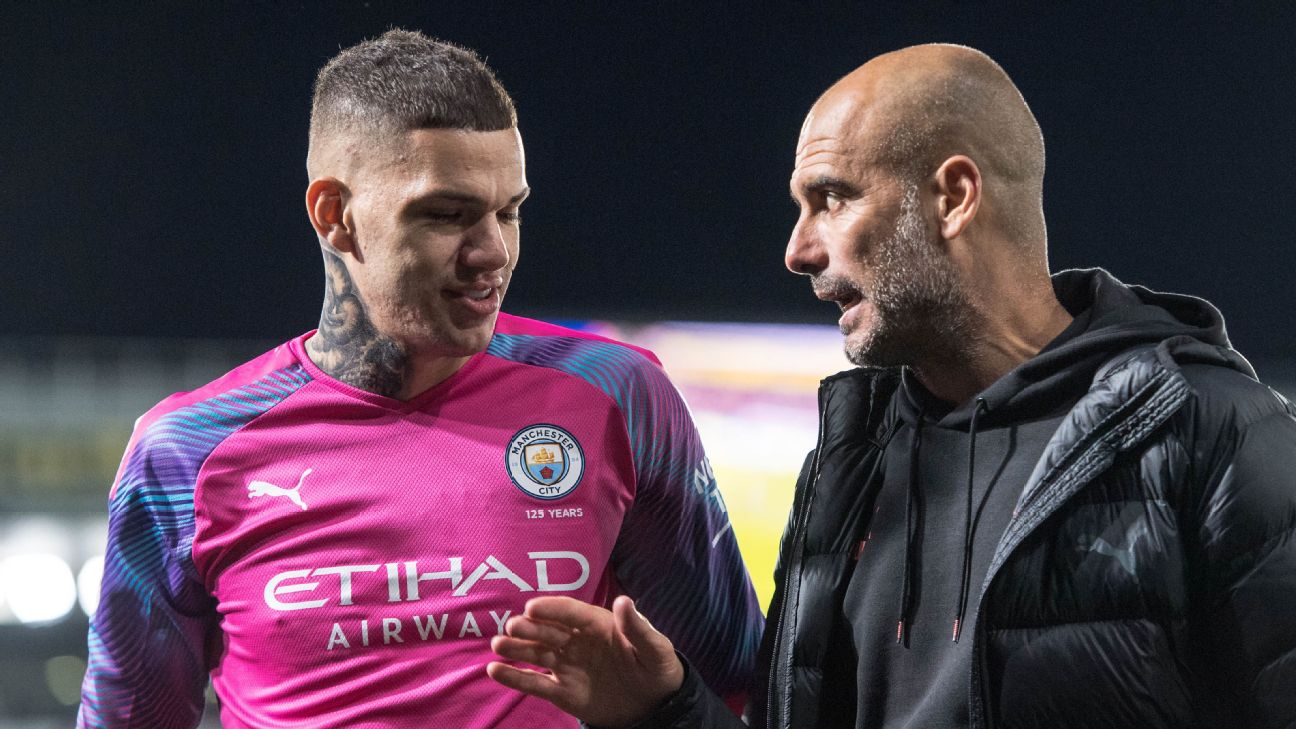

It’s clear from his playing style that Ederson really flourished once he landed in Europe. Back in Brazil, Rogerio Ceni might have been superb with the ball at his feet but free-kicks aside, he was mostly a penalty area keeper. Defensive lines in Brazil tend to play deep. In Europe, the big teams will play a much higher line and for some of these teams, the keeper has taken on outfield duties, taking responsibility for things some distance from his goal. This comes naturally to Ederson and is one of the main reasons Pep Guardiola bought him. He acquired a keeper who can complete short passes and control possession comfortably, is so good at his long-range distribution that he has assists to his name and is also happy to come out of his area. This is something Alisson has worked on with some success since he has been in Europe, but Ederson has more to offer as an auxiliary midfielder.

Even so, there’s no doubt that Alisson is Brazil’s first choice. Ederson accepts that he is the reserve. He was an unknown in Brazil when Alisson took over the position, the Liverpool man has never let his country down and his importance to Liverpool’s Champions League triumph was clearly apparent. The pair are friends and colleagues; theirs is a lonely position and the “goalkeepers’ union” usually forges bonds between shot-stoppers that transcend club and country allegiances. But they are also rivals. Ederson acknowledges that Alisson is currently in front of the queue, which means that it is up to him to work hard and well enough to reverse the order.

Happy is the coach who can rely on the friendly competition between two of the world’s best goalkeepers.