Products You May Like

In the summer of 2018, Juventus was enjoying an unprecedented domestic run. The Bianconeri racked up 95 points in Serie A play to win their seventh consecutive league crown, and they destroyed AC Milan, 4-0, to win their fourth consecutive Coppa Italia.

Paulo Dybala, 24 years old, was emerging as one of the best young strikers in the world, recording 22 goals and five assists in league play. Veteran Gonzalo Higuain added 16 and six. Creation was coming from everywhere — new winger Douglas Costa had 12 league assists, and six other players recorded at least four — and the defense was still prototypical Juve, allowing a league-low 24 goals in 38 games.

And yet, the restlessness was overwhelming. For all their domestic success, Juve had consistently fallen just short in the Champions League, a tournament they hadn’t won in more than 20 years. In 2015, they beat Cristiano Ronaldo‘s Real Madrid, but lost in the finals to Leo Messi’s Barca. In 2017, they pounded Barca, but lost 4-1 to Real Madrid in the finals. In 2018, they finished second to Barca in group play, then fell in the quarterfinals to Real Madrid.

– Report: Juve, Ronaldo knocked out of Champions League

– Pirlo: Juve project continues despite UCL exit

– Former Juve player, manager Capello: Ronaldo “the worst” in Juve’s elimination

It was an albatross even during extraordinary success, and in a bold attempt to solve the problem, the club used pretty simple logic: if winning the Champions League requires either Ronaldo or Messi — one of their clubs had won five straight titles and seven of the last 10 — then it was time to go get one of them. In both transfer fees to Real Madrid and salary, they decided to invest nearly $400 million for the then-33-year old Ronaldo.

In the nearly three years since:

– Their Serie A streak has continued … for now. Their point total fell to 90 in 2018-19 and 83 in a narrow win last season, and they’re currently on pace for 79 and a third-place finish.

– Their Coppa Italia streak ended with a quarterfinal loss in 2019, and they lost in the finals in 2020.

– They were eliminated from the Champions League in the quarterfinals in 2019 and in the round of 16 in both 2020 and 2021. Bad luck in the draw? No. Instead of losing to Real Madrid or Barca or Bayern Munich, they’ve fallen to Ajax (2019), Lyon (2020) and now Porto (2021).

It’s safe to say this hasn’t worked out as planned. Instead of unlocking past glory, Juve have just gotten older, more expensive and a little bit worse. They’ve found themselves stuck between win-now mode and a rebuild, and their biggest issue is one that might be hard to solve with their best player remaining on the roster.

Ronaldo is doing what he’s paid to do

Since Ronaldo signed with Juve, here’s the list of players who have produced more goals than his 86 in “Big Five” league play and UEFA competitions: Bayern’s Robert Lewandowski and Messi. That’s it. If we’re looking at combined goals and assists, it’s Messi, Lewandowski and PSG’s Kylian Mbappe.

Ronaldo is now merely one of the best goal scorers in the world, and while his Ballon d’Or-winning days might be over, he’s also 36 and still in the best-in-the-world conversation.

– Marcotti: Juve’s elimination doesn’t change that club on right track

This year is almost certainly his best yet in Turin. He’s on pace for about 30 league goals and five assists, one year after producing 31 and five, but 12 of last season’s goals came from the penalty spot. This year, that number’s down to four; he’s on pace for 24 non-penalty goals, his most since 2016 in Madrid, and his 0.136 xG per non-penalty shot is his highest average on record.

Ronaldo is picking his spots better than ever and putting the ball in the net. Overall, Juve is averaging 2.04 goals per match, its second-best rate in the last seven seasons. Granted, league-leading Inter are averaging 2.42, but offense might not be Juve’s biggest issue.

The possession game requires pressure

Despite the “win-now” move of signing Ronaldo, Juve have also spent the past couple of years attempting to modernize its footballing philosophy. Maurizio Sarri replaced Massimiliano Allegri in 2019-20, but didn’t perform to everyone’s liking, so the club hired first-time manager and former Juve midfielder Andrea Pirlo to implement his beautiful, possession-based vision.

As Gab Marcotti noted, you probably don’t hire a first-time manager if you’re only thinking about the short term, and it doesn’t immediately appear as if Pirlo will get sacked for either his team’s Champions League failure or the impending end of Juve’s Scudetto streak.

It probably helps Pirlo’s cause that you can see his vision mostly coming to life. If we compare their league stats to those of the rest of the top 20 in FiveThirtyEight’s latest club soccer rankings — a list that includes about 16 or so teams with a professed possession vision — we see that they get most of the basics right.

– Possession: Among these teams, Juve rank fourth in average possession time (28.8 seconds), sixth in average passes per possession (6.8) and sixth in pass completion rate into the attacking third (76.0%). They attempt few long passes (8.1% of all passes, fourth) but complete the ones they try (64.0% completion rate, second).

– Offensive quality: They rank second in average shots per possession (0.19) and fifth in xG per shot (0.14).

– Overall quality: Most importantly, they rank seventh among this group in goals scored (2.04) and eighth in goals allowed (0.84).

This has all happened mostly without Dybala, who has logged only 646 minutes in 11 league matches because of thigh problems, then an MCL injury. After struggling to integrate with Ronaldo in 2018-19, Dybala improved in his new complementary role, recording 11 goals and six assists in 2019-20; in 2020-21, he has only two and two. His return would offer an already solid attack a little bit of extra pop.

So what are the problems, then? Why are they fielding what will likely end up their least successful overall team in a decade? Two things, perhaps: poor fortune and poor pressure.

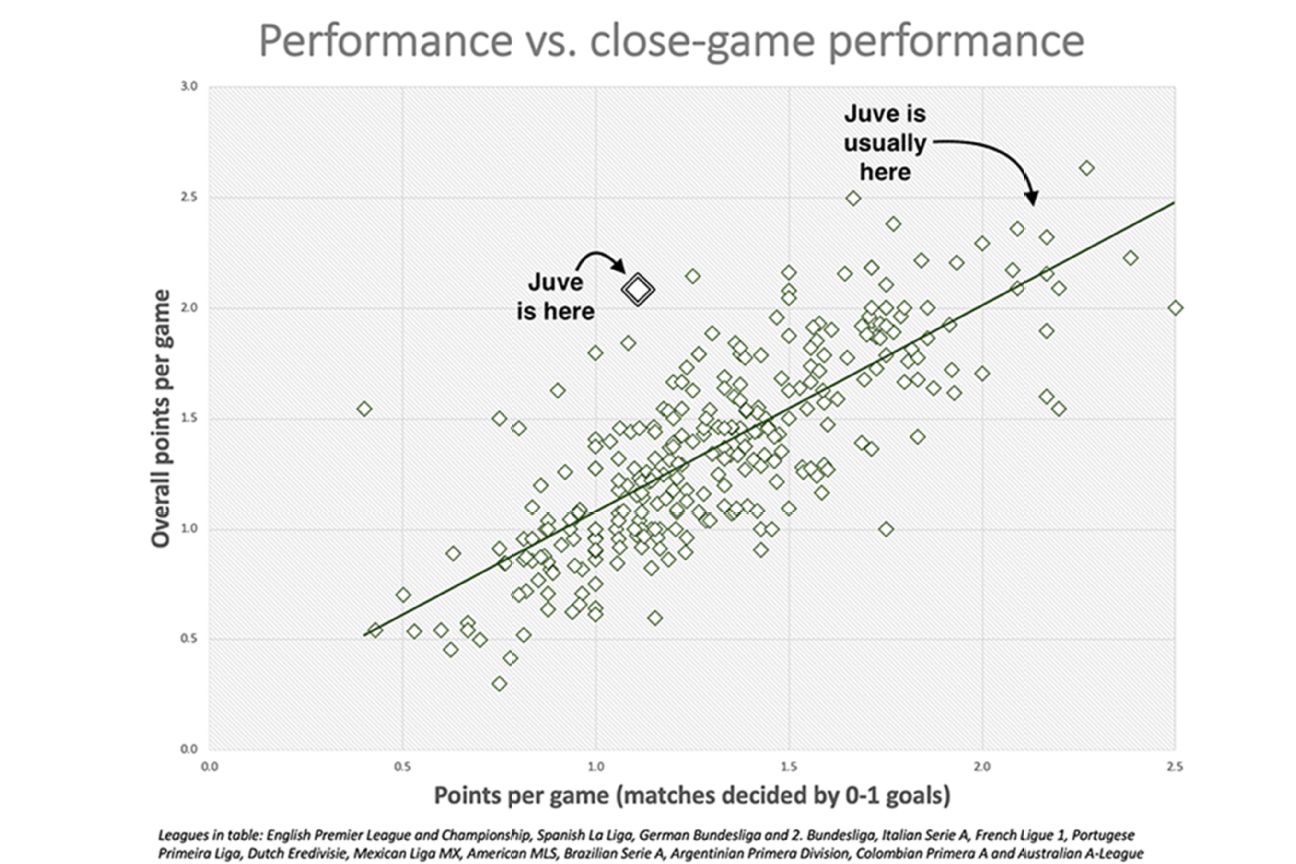

Few have enjoyed more close-game success than Juve through the years. Antonio Conte’s 2013-14 squad averaged 2.67 points per game in matches decided by zero or one goals, a level of success that puts even last year’s Liverpool (2.50) to shame. That was unsustainable even for a good team, but Juve have averaged at least 1.83 points in such matches every year since. They were at 2.14 last year.

This year: 1.11 points per close game, 12th overall in Serie A and by far the lowest among the league’s top nine teams. They’ve played in nine games decided by zero or one goals — one win, one loss and seven draws. With more normal close-game fortune (say, 2 points per game), they’d be two points back of Inter at the moment instead of 10.

Close-game performance is a regression factor of sorts: too much success is a sign of impending regression and vice versa. Juve’s average will progress toward the mean at some point, even if it’s already probably done too much damage to keep the Scudetto streak alive.

It’s not all poor fortune, though. While the overall defensive numbers are fine, they’ve kept only eight clean sheets in league play and are on pace for about 12 for the season. They achieved this 17 times in Allegri’s last season, 22 the year before Ronaldo’s arrival. Six of their draws have come via a 1-1 score, the seventh 2-2; it’s fair to assume some of those would have been 1-0 or 2-1 in previous seasons.

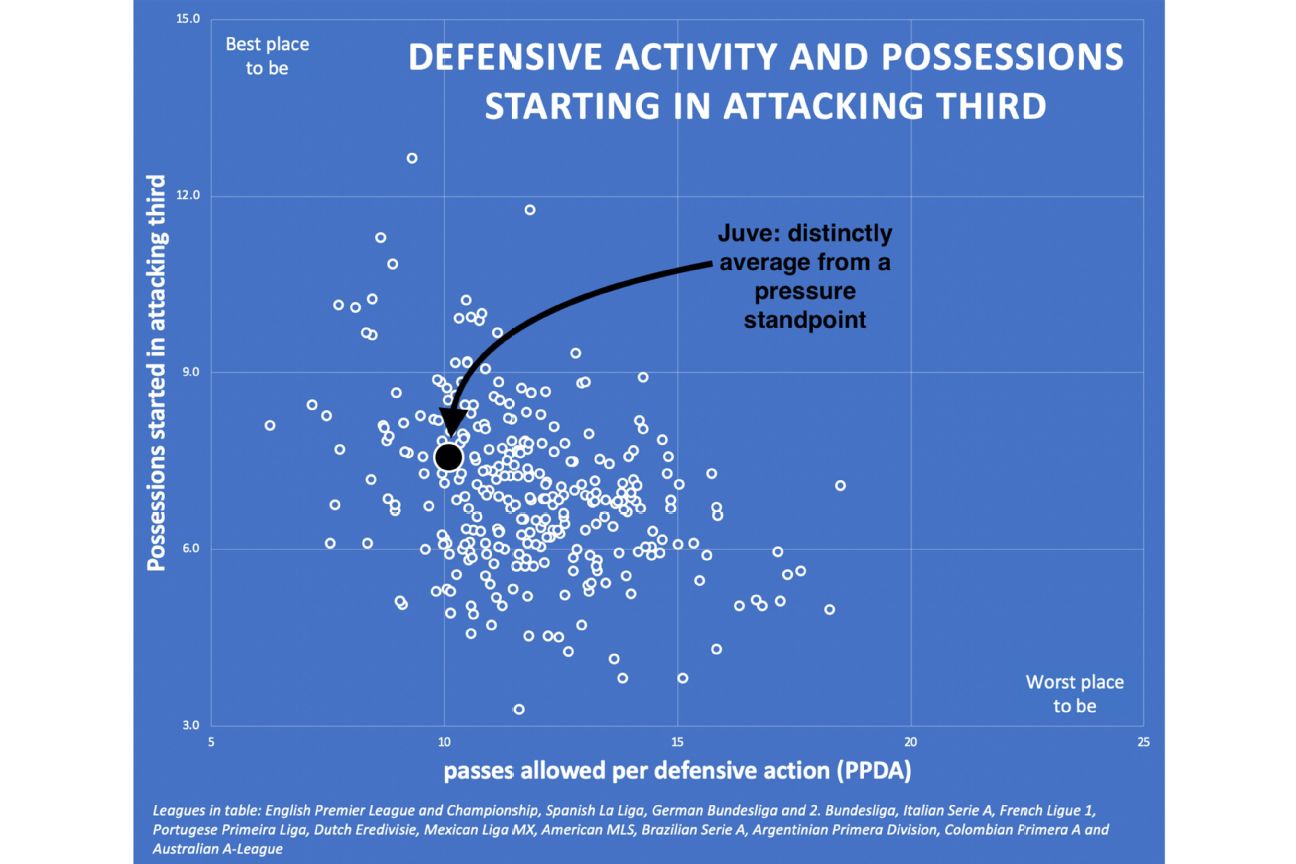

It’s always going to be tricky transitioning from a more compact and standard defensive structure, to the riskier high defensive line deployed by most high-level possession teams. Typically, this approach results in teams allowing low shot quantity because the ball spends a lot of time far away from your defensive third — either you’re in possession of it on your opponent’s side of the field, or your opponent takes the ball back and you engage in counter-pressing. When opponents break the pressure and engage in a solid counter-attack, it can produce occasionally high shot quality (as measured by xG per shot), but you don’t allow many shots overall.

Juve, on the other hand, allows more shots per possession (0.13) than anyone in FiveThirtyEight’s top 20 besides Tottenham Hotspur. The best teams in the world typically average 0.10 or lower; Manchester City currently allows 0.08, which results in about five fewer total shots allowed per match than Juventus.

Granted, Juve don’t allow high-quality chances (their 0.10 xG per shot allowed is the best among these 20 teams), but when you combine this with the fact that their opponents only lose 34.6 possessions per game from their defensive third (second-lowest among this 20) and finish 39% of their possessions in Juve’s attacking third (third-most), you start to realize that Juve simply do not pressure the ball the way that the best possession teams do.

Of course, this isn’t on Ronaldo, because you do not sign Ronaldo to pressure the ball. That’s never been his game. He has not averaged more than 2.2 ball recoveries or 4.1 total defensive interventions (ball recoveries, tackles, interceptions, clearances, blocked shots, blocked crosses, aerials won in the defensive third) per 90 at any point in the past eight seasons. This year’s averages of 2.1 and 3.2 are right in line with expectations.

Of course, Lewandowski isn’t much for ball recoveries either, but he’s got Alphonso Davies, Leon Goretzka and Joshua Kimmich (combined: 29.4 ball recoveries per 90, 4.3 in the attacking third) around him for that. Mbappe has Idrissa Gueye, Rafinha and Marco Verratti (24.0 and 2.5, respectively). Inter’s Romelu Lukaku has Arturo Vidal and Nicolas Barella (13.5, 1.9).

Yet Ronaldo doesn’t have nearly as many true “havoc creators” around him. Rodrigo Betancur, Danilo and Matthijs de Ligt (combined: 21.6, 0.6) are solid in this regard but don’t play particularly far up the pitch. Arthur (7.5, 1.1) can pressure the ball at all levels but has battled injuries for the past three months and has produced nothing offensively: he averaged 0.46 goals and assists per 90 at Barcelona last season, but is currently at 0.10 this season. Whether Ronaldo is in black and white next year or not — he’s got a year left on his contract, and if they tried to sell, there wouldn’t be many takers given the financial conditions in world soccer — it would behoove the club to find a “chaos agent” to add to the mix.

1:53

The FC guys chime in on the numerous disappointments in Juventus’ Champions League exit in the round of 16.

Lo! A youth movement emerges

In a way, you could view the Ronaldo signing as the intended end to a cycle. Since about 2014-15, the Juve squad has been on the older side: among players logging at least 1,000 minutes in league play between 2014-15 and 2019-20, only an average of 3.3 were 24 years old or younger, while 6.8 were 30 or older. A lot of these 30-and-older guys were really good, of course, but landing Ronaldo for one final run at glory before blowing the roster up might make sense in some way.

Just as that “run of glory” never really commenced, though, Juve also haven’t waited until Ronaldo’s departure to begin the inevitable youth movement. Over theplast two years, the club has sent away 30-and-older stars Gonzalo Higuain, Blaise Matuidi, Mario Mandzukic, Miralem Pjanic and (via loan) Douglas Costa while bringing in the following players:

– Defenders Matthijs de Ligt (21) and Merih Demiral (23) from Ajax and Sassuolo, respectively

– Midfielders Federico Chiesa (23), Arthur (23), Weston McKennie (22) and Adrien Rabiot (25) from Fiorentina (on a loan-to-buy deal), Barcelona, Schalke 044 and PSG

– Forward Dejan Kulusevski (20) from Atalanta

That’s a lot of fun, young talent in three transfer windows.

You can currently see a balancing act taking place. Juve’s top four minutes earners in league play are all 29 or older, and that doesn’t include Ronaldo or surging 32-year old fullback Juan Cuadrado, who was, for my money, the best player on the pitch against Porto on Tuesday.

– Stream ESPN FC Daily on ESPN+ (U.S. only)

– ESPN+ viewer’s guide: Bundesliga, Serie A, MLS, FA Cup and more

At the same time, eight players currently 24 or younger are on pace for 1,000+ minutes. Chiesa and Kulusevski lead the team in chances created (McKennie is seventh), Betancur and de Ligt are second and fourth, respectively, in ball recoveries (McKennie is seventh again), Demiral has been key in moving the ball between defensive lines toward midfield (93% completion rate to the middle third), and Arthur, de Ligt and McKennie have all thrived in moving the ball from the middle third to the attacking third.

(A word on McKennie: the U.S. star has truly been a jack of all trades in the middle of the field, not only progressing the ball and creating occasional offense, but also winning 54% of his duels, 60% of his aerials and 65% of his tackles in the middle third.)

Dybala is still only 27 and has prime years remaining if or when he can return to full strength, and other key pieces like forward Alvaro Morata (28 years old) and fullback Danilo (29) aren’t exactly ancient. They still need another “chaos agent” to win the ball, and goal scorer to account for Ronaldo’s eventual departure, but they seem to have a lot of what they need if they can remain patient and keep these young players on proper developmental trajectories.

“Patience” is a new word quite a few mega-clubs have had to learn over the past year. In recent history, talking about Juve required a contradiction between referencing a positive present and an unclear future; now it appears it’s the polar opposite. That might mean fewer trophies in the near future, but perhaps it will help the next big run at glory bear more fruit.