Products You May Like

When someone who’s unfamiliar or only slightly familiar with the sport of soccer asks me who is the best player in the world, I tell them “well, it’s Lionel Messi.”

Then, when they say “why?” I say “he’s the best goal scorer I’ve ever seen, and since goals are so scarce and so valuable, scoring goals is the most important thing a soccer player can do.” That’s usually enough, and I’ll get some kind of “OK, got it. Thanks.” But then, I’ll keep talking: “And he’s best at creating goals for his teammates. And he’s the best passer. And he’s the best dribbler. And he’s the best free-kick taker, too.”

While my viability as a pleasant conversational companion is obviously in question, Messi’s greatness is not.

In fact, his omnipotent effect on games reminds me a bit of The Great One, Wayne Gretzky. His dominance over hockey can be summed up with one line: If Gretzky had never scored a goal, he’d still be the sport’s all-time leader in points. He just happens to be the sport’s all-time leading goal scorer, too. Meanwhile, in Europe’s Big Five leagues since 2014, Messi has scored the most goals, bagged the most assists, played the most through-balls and completed the second-most dribbles.

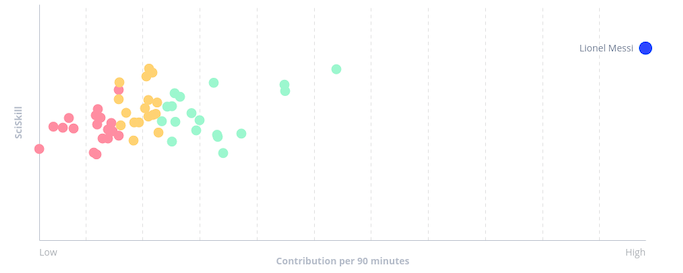

It goes beyond those numbers. Last year, a group of researchers in Belgium and the Netherlands published a paper that aimed to put a value on every on-ball action that occurs in a match. For example, they write that “an action valued at +0.05 is expected to contribute 0.05 goals in favor of the team performing the action, whereas an action valued at -0.05 is expected to yield 0.05 goals for their opponent.” Their research for the 2017-18 season found Messi to be the highest-rated player in Spain — by far.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the research said that most attackers produced a limited number of actions but that those actions were of high value, while midfielders did the opposite: lots of low-value actions. There was, of course, one player who excelled at both. “Lionel Messi is an outlier in the sense that he rates high on action quality and quantity at the same time.” Hell, there’s even a well-respected paper that suggests Messi is better at walking than everyone else, too.

So, we have to ask: Is there anything Messi isn’t good at?

It’s evident that Messi is not a great defender, but you already knew that. Since 2010, he has never recorded more than 23 tackles or 22 interceptions … in an entire La Liga season. He also rarely wins back possession for his team. But part of that can be attributed to the fact that Barcelona have heavily dominated possession in the majority of the matches he has played for the club. Plus, a number of Messi’s teams have been among the most effective pressing sides of the past decade, and pressing doesn’t work too well if everyone on the field isn’t taking part. So, he has at least been a capable member of effective, aggressive defensive units in the past.

So, he has pressed in the past, but he has barely done anything in the defensive third. Since 2010, he has cleared five balls, blocked five shots and blocked one cross – total. But any time Messi has to actually do any of those things, there has likely been a brief systematic failure to his team’s play. You want him near the opposition goal, not your own. Sure, he’s probably a terrible goalkeeper, too, and any coach who plays him there is a perverted sadist, but what about the things he is supposed to do? Creating goals, dribbling and passing: Is there anything within those facets where Messi’s mortality starts to shine through?

Now we’re getting somewhere.

For a start, he’s not a great crosser of the ball. “In the 2018-2019 Primera Division, Messi tops the charts for shots and passes and ranks second behind Vinicius Jr. for dribbles and take-ons,” said Jan Van Haaren, one of the authors of the value-based paper mentioned above. “In terms of total contribution per 90 minutes from crosses, Messi ranks in the middle of the pack.”

Last season, Messi completed just 14 of his 78 crosses, which tied for 84th and 50th in La Liga, respectively. His completion percentage of 17.9 was below the league average of 23.9%. However, crossing tends to be one of the more inefficient ways to score and if you were picking one aspect of attacking play to be average at, this would probably be it.

Van Haaren is the chief product & technology officer at SciSports, an analytics company that, among other things, uses the framework from the paper he co-wrote to rate players. Even with the middle-of-the-pack crossing, Messi might as well have been playing a different sport last season, according to the model’s rating of his overall contribution compared with other wingers and midfielders:

The graphs for the two seasons before ’18-19 look almost identical, too.

Most semi-advanced soccer data begins around 2010, but earlier this year, another analytics company, StatsBomb, went back through the tape of every game Messi has played for Barcelona, charted all of the actions and then released the dataset to the public.

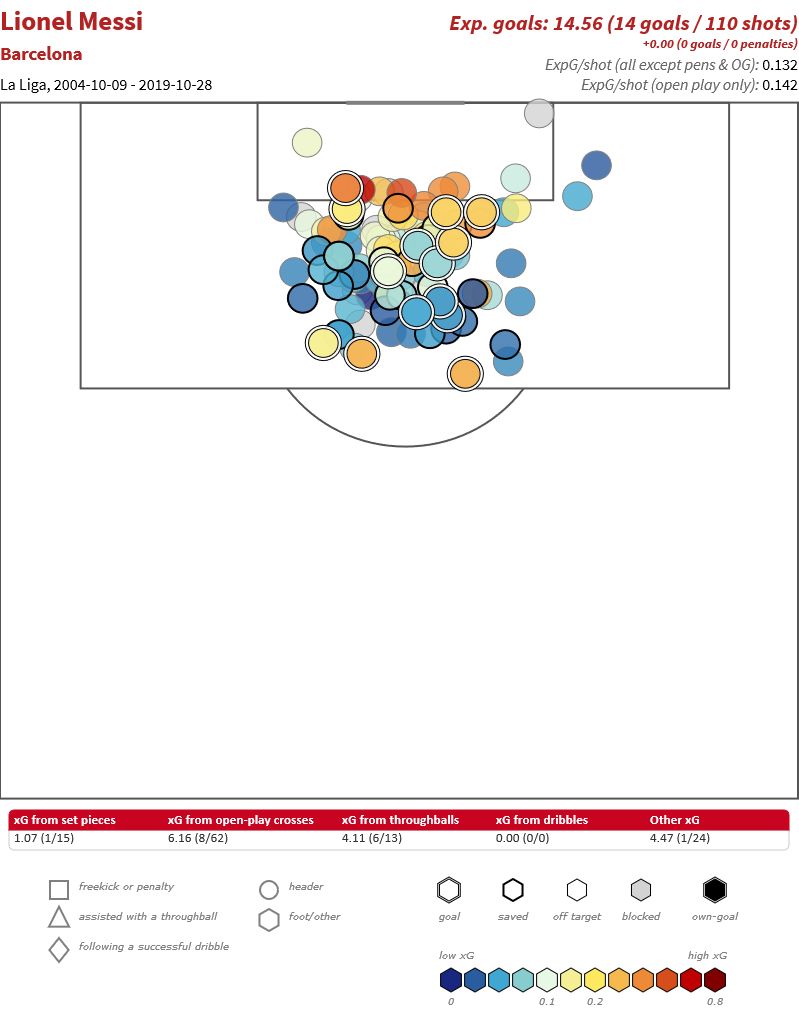

Another thing Messi is just average at? Scoring on headers. These are all of his attempted headers since his La Liga career began, per StatsBomb:

“He basically scores headers at an average rate: his goals roughly equal his expected goals, and he gets about one per season,” said James Yorke, head of analysis at StatsBomb. Much like crossing, heading is another less-efficient thing Messi isn’t great at — a shot with a foot from the same location as a shot with a head is much more likely to be converted — so he just rarely tries to do it. After all, he’s not even 5-foot-7.

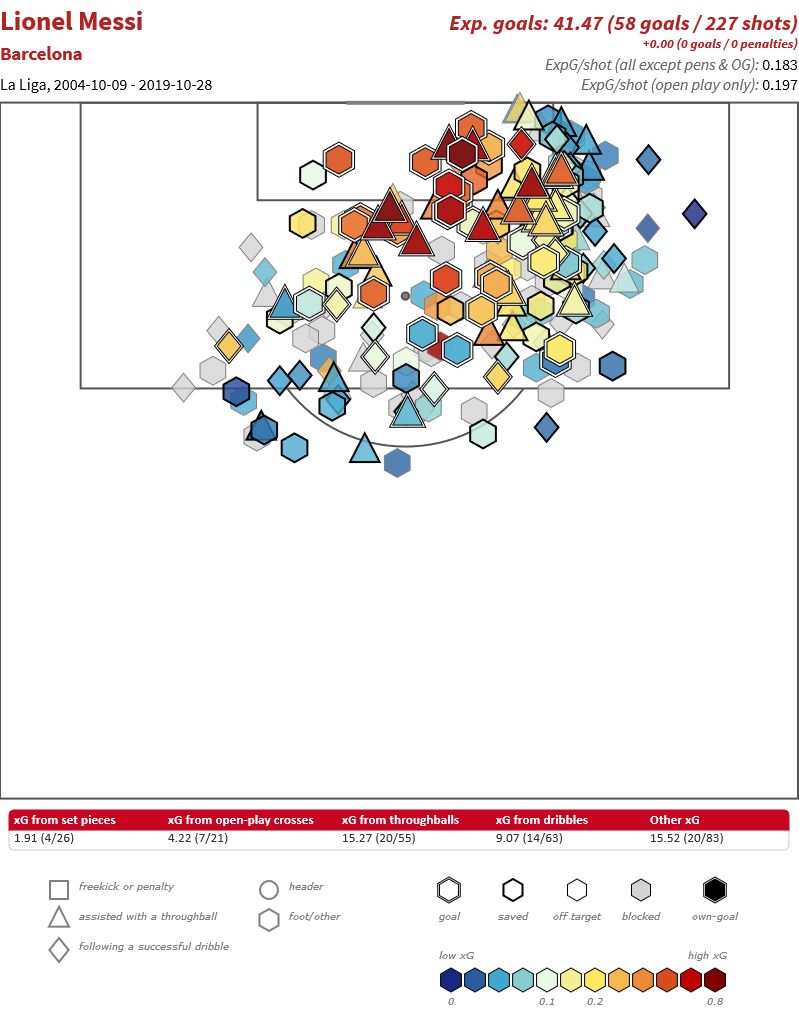

The majority of Messi’s goals and shots come from his left foot, but even when he uncorks one with his off peg, the result remains deadly.

According to StatsBomb data, he has scored 58 goals with his right foot on chances worth just 41.47 expected goals. However, there is one hole. One of Messi’s trademark finishes is getting deep into the box, cutting in from the right and letting rip with his left from the corner of the 6-yard box. The reverse rarely happens, as this map of all of his right-footed shots in La Liga shows:

“What this tells me is that he’s never found himself deep on the right side, cut onto his right foot and shot,” Yorke said. “If he had, we would see some shots in that zone. Evidently, and probably wisely, he has always engineered a shot with his left foot or a pass, but it’s a funny little quirk nonetheless.”

And so, as Messi ages deeper into his 30s and (presumably) starts to decline, a look at his minor inadequacies helps to explain just why he’s so great in the first place: The things he isn’t good at don’t matter as much, and when he can’t do something better than everyone else, he makes sure he barely has to do it at all.