Products You May Like

On April 6, 1996, Major League Soccer held its first match. D.C. United traveled to the San Francisco Bay Area to take on the San Jose Clash, with the hosts securing the first win in the league’s history thanks to an 88th-minute Eric Wynalda winner. Were it not for the coronavirus pandemic putting the sports world on hold, MLS would be in the midst of celebrating its 25th season, complete with what would have been a rematch of that inaugural game, as the San Jose Earthquakes were originally scheduled to host D.C. on Saturday.

To relive those days and help contextualize just how much MLS has grown in that span of time, we spoke with those who were there at the beginning during the “Wild West” days of American soccer’s top professional league in the modern era. From stolen cars to cramming into planes next to families and being mistaken for college sports teams, from team barbecues to training in parking lots, it was a far cry from the polished product of the modern era.

These are the stories of the people who got the league off the ground, who oversaw its inception, who played in its first games. This is their history of the inaugural season of Major League Soccer.

The beginning

At its outset, Major League Soccer was a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants operation. Contracts were signed before the league had formally begun; executives joined teams with no other title than “TBD”; and apart from a $5 million loan, MLS lived and died by the checkbooks of its clubs’ owners.

Sunil Gulati (MLS deputy commissioner, 1996-99): When people say, “What was the toughest part of that?” it was that you were doing everything from scratch on a very short time frame. That was really the main challenge. We were trying to raise money, trying to get coaches, general managers, players, decide on cities, sell tickets, have sponsors, have a TV partner, all before we had a league. And so literally, we had TV partners committed and some sponsors committed before we were closed on the deal, and players certainly agreed [to contracts] well before we were closed and officially had financing.

Charlie Stillitano (New York/New Jersey MetroStars general manager, 1996-99): I ended up taking the job as the head guy of the New York/New Jersey MetroStars. I think my title was vice president and general manager. There was no president; we were learning as we go, if you will.

Alexi Lalas (New England Revolution, New York/New Jersey MetroStars, Kansas City Wizards, LA Galaxy defender, 1996-2004; president and GM, San Jose Earthquakes, 2004-05; GM, New York Red Bulls, 2005-06; president and GM, LA Galaxy, 2006-08): For a number of years, we had talked about it in the backs of buses and in bars and on flights about what this would look like. And I think there was a collective type of acceptance of responsibility that if it was gonna work, we not only needed to be a part of it, but a lot of us — and I was part of that group — wanted to be here. One of the proudest days of my life was getting on that plane in Italy and flying back to Boston for the start of the league. So not to get too dramatic about it, but it was like la cosa nostra, it’s our thing, so it wasn’t as difficult as it sounds, and it still remains one of the proudest things that I’ve done.

Tony Meola (New York/New Jersey MetroStars, Kansas City Wizards, New York Red Bull goalkeeper, 1996-2006): When they did an unveiling of uniforms in New York City, that was really the first time I thought “okay man, this is a go.” Because I had been waiting for it… we were supposed to start the league in 1995, as you know. I was kind of stuck, and really got bailed out by the Long Island Roughriders with an opportunity to play for Alfonso Mondelo and that group of guys that was there, a lot of those guys played in MLS down the road, and I was at, that point, a little bit skeptical as to if this thing was going to go or not. And it was at that event that I was like we’re finally going to get this thing off the ground.

Gulati: We had a $5 million loan from World Cup USA [the organizing committee responsible for USA ’94], and then the rest came from the investors, the original owners. They were in for units of $5 million apiece.

Building the teams

It was hard to build teams without a league, and as clubs began actively recruiting, signing those players proved a complex and convoluted process. Tab Ramos was sent on loan to Mexico from MLS, despite possessing a contract that didn’t contain any figures. Alexi Lalas played in Italy and 24 hours later was a second-half substitute in Boston. Countless players were signed sight unseen.

Cobi Jones (LA Galaxy midfielder, 1996-2007; LA Galaxy assistant manager, 2008-10): [I had] a few options: The team in Brazil [Vasco da Gama] wanted me to stay there. I think they wanted to see if they could sell me in Japan. So those were the choices: Mexico, Japan or come back to the start of [MLS]. I don’t think it was a difficult choice for me considering my initial thought, from the beginning, was that I would be out [in the world] for the year or two [after the World Cup], as we were all kind of trying to figure out when MLS was going to start. But [I decided] just to come back and help start MLS.

Gulati: Remember, we allocated certain players to teams before they had coaches. I remember [Ajax, Barcelona and Netherlands men’s national team manager] Rinus Michels saying to me, because we had allocated [Colombia star midfielder] Carlos Valderrama to Tampa, and we were talking about that, and he said, “Listen, I can imagine a situation where certain coaches don’t want to build a team around the player they’ve been allocated.”

Stillitano: I’m friends with Sunil Gulati today, and I have a lot of respect for him. He did a lot for the league and was very influential. But one of the jokes around the league in that first year was that MLS stood for “More or Less Sunil.” Sunil was the deputy commissioner, and you lived and died with what Sunil gave you. You’d make trades, and he could kill them. Honestly, a lot of the rules seemed to be rules that were flexible and convenient. They would make decisions what they felt were best for the league, and Sunil was in charge of that area. There were trades that were blocked, trades that were encouraged. I think there was a lot of involvement from the league — no other way to put it. You know they felt that the best way to fix a team was to either help them with players or help them with the manager.

Gulati: The majority of players in that first year, on day one of preseason, were players who had been picked after a multiday combine and some players who were obviously allocated that people hadn’t seen themselves directly. What I mean by that is, I don’t know how much of Juan Berthy Suarez that Bruce Arena had seen personally. But we had seen him, because we knew he’s the leading scorer in Bolivia.

Garth Lagerwey (Kansas City Wizards, Dallas Burn, Miami Fusion goalkeeper, 1996-2000; Real Salt Lake senior vice president and GM, 2007-14; Seattle Sounders president and GM, 2015-present): [During the combine] I think we did the physicals on the field. You were literally going from like one small-sided game to another, almost like stations in this huge open field, and I think we just rolled out the balls for small-sided games. And I remember Bob Gansler pulling me aside at some point and Bob was from Wisconsin, and I was from Illinois. We kind of knew each other coming up through that part of the world; he had given me some good feedback. I felt reasonably good at the combine that I might make it through. I went to the draft and was picked 150th out of 160 picks — still the lowest draft pick to survive in MLS history. I was the MLS version of Mr. Irrelevant. In all five years I played, I was the lowest draft pick. Full stop. As my friends like to tell me, I was the least talented player ever to play.

Richie Williams (D.C. United, New York/New Jersey MetroStars midfielder, 1996-2003; New York Red Bulls assistant coach, 2006-11; Real Salt Lake assistant, 2015-16; New England Revolution assistant, 2019-present): I was actually staying at Bruce Arena’s home [in Charlottesville, Virginia] because I was training there and working … Bruce was not home; he was coaching the Olympic team and had an extra room I was able to stay in while I trained. The combine was in January … I remember getting a phone call from Dallas; they were potentially interested in drafting me, and they kind of asked me, would you rather be drafted by Dallas or D.C. … and I said you know, listen, I’m just very happy to be drafted by anybody. Of course, my first choice would be New York or D.C., just because I was from New Jersey, and I went to school at the University of Virginia, but I wanted to be drafted and have the opportunity to play.

Gulati: [Signing] Tab Ramos was interesting. I had come back from Europe, flown into Raleigh-Durham for a wedding on New Year’s Eve. Dean Linke, who was the press officer for the Colorado Rapids at the time, was getting married. I met Tab the next day in Dallas, we flew together to Monterrey [Mexico], where he was eventually going to sign with Tigres. And I was just helping them, frankly: We’ve known each other a long time, and he trusted me. And sort of a day into the negotiation I turned to Tab and said, “Why don’t we do this as a loan?” And he said, “From who?” And I said, “From the league we’re trying to start.” We actually set it up as a loan without having a deal done with MLS.

So we shook hands and therefore had a contract that didn’t have numbers in it because we didn’t know what the deal was going to be. And so technically, we loaned him, from a league that hadn’t started yet, to Tigres. And that was partly to give him some protection to be able to come back if there were any issues.

– Stream ESPN FC, 30 for 30 Soccer Stories and much more on ESPN+

– Henry is trying to resurrect his coaching career in MLS

– Zimmerman laying down roots in Nashville amid city’s tragedy

Lagerwey: I still have the T-shirt from that combine, because you got a number usually like a three-digit number, so the scouts can tell you apart. I saved that T-shirt. I still have it.

Gulati: Another memorable [signing] is [Mexico goalkeeper] Jorge Campos. I’d met with him already a couple of times. I knew the president of his club [Atlante]. We finally signed a deal when I was in Mexico. At the last minute, we’re literally getting documents printed back in the States while I was at his apartment, and I guess they were being faxed to us. He said, “Hey, I gotta have a car and an apartment to live in.” So we said, “Yeah, of course, that makes sense.” So he signed. And then when he came, you know, the first game he put 69,000 people [in the stands]. First game he played in, he was actually playing in two leagues at the same time, which looking back, certainly a violation of FIFA rules.

Lalas: I remember being in Italy and pulling up my America Online account, doing the whole dial-up, and eventually I get the signal, and then seeing the names of my future teammates in New England. And I remember calling a player by the name of Tommy Lips. Wonderful character, and I’ll never forget he hung up on me because I proceeded to call all these guys to just reach out and touch base, and he hung up on me, called me a nasty name and thinking that it was one of his friends playing a prank on him.

Gulati: [Agent] Richard Motzkin and I were negotiating [signing Alexi Lalas] for quite a while. In his first year at Padova, Alexi was playing in a relegation game. If I’m not mistaken, he gave up a penalty kick or scored an own goal and then converted a PK in the penalty shootout. Bottom line, it’s on a Saturday. [I’m in Florence] the game finishes, Alexi and I drive to Milan that night, stay in a hotel. The next morning, we fly through London to Boston. The reason? We’ve got U.S. Cup the next day. It was U.S. Cup ’95, and we want Alexi to play in it because it will help sales. So literally, we get to Boston Logan. We’re not with a police escort — we’re in a police cruiser. Alexi and I in the backseat of a police cruiser, state cop. He gets us to the stadium. Alexi gets dressed and plays in the second half of the game.

Lalas: This was “Wild West” stuff, not for the faint of heart. But there was a general cautious optimism. Our history, and our background, is littered with failed teams and leagues. But I’d be lying if I told you that we envisioned what I look out and see in 2020 now when it comes to what MLS is on or off the field.

First experiences

The soccer fever that gripped the United States when it hosted the 1994 FIFA World Cup quickly reemerged in the early days of Major League Soccer: Tailgates, fireworks and packed stadiums greeted stars. There also was one star’s insistence on getting a Ferrari for joining the league — and the league giving it to him.

Jeff Agoos (D.C. United, San Jose Earthquakes, New York/New Jersey MetroStars defender, 1996-2005; New York Red Bulls technical/sporting director, 2007-11; MLS technical director of competition, 2011-present): I think just the newness of everything was just completely wild. I went back and rewatched [D.C. United vs. San Jose], at least parts of it. And it was a terrible game. I mean, it was really not what you’d want to watch and say, “Hey, this is why MLS is going to be good.” And I think part of the thing we were really trying to avoid was to not have a 0-0 tie at all costs, because the biggest issue with the public was that, “Soccer is a boring game, there’s not a lot of shots on goal. Games end 0-0.” So, Eric [Wynalda] scores the goal with about five or six minutes to go. He goes around me and then shoots. I would like to go on record saying that I single-handedly saved the league from its demise in its early years. I want to get recognition for playing my part in making sure MLS got to 25 [seasons].

Jones: I think I’ve said it 1,000 times, I think it was beyond everybody’s expectations. And for me personally, it was beyond everything that I could have possibly imagined. I think it blew away everyone’s expectations just considering where we were just starting off a league. For me, it was like being at a World Cup again. [In the parking lots] people were grilling, playing soccer, people were just hanging out and just tailgating, and that was unexpected. The excitement and I think sense of awe could be felt; it was palpable.

Peter Vermes (New York/New Jersey MetroStars, Colorado Rapids, Kansas City Wizards defender, 1996-2002; Kansas City Wizards technical director, 2006-09; Kansas City Wizards/Sporting Kansas City manager, 2009-present): I played in the first game at the Rose Bowl. It was awesome. They were turning people away at the gate because they had sectioned off a huge amount of seats behind one of the goals because they were doing a big firework show at the end of the game. They just didn’t have enough people at the ticket lines, because they didn’t expect that many people showing up for the game.

Gulati: [Jorge Campos] came in on Monday after that weekend’s first league game and he said, “I want to talk to you about the car [I negotiated to join MLS].” And we said, “Yeah, great, we got a few Hondas that we bought for people.” I don’t know the exact language, but bottom line is he didn’t want a Honda. He wanted to get a Ferrari. A year or two later, when [we did] an internal audit, they said, “You know you bought all these cars, Hondas or whatever Hyundais, but this one guy got a Ferrari. We kind of explained that there were 69,000 people at the game. Campos came in on Monday and said, “If you’d like me to come back next Saturday, I would like a Ferrari.” And he got the Ferrari.

At the time I was like, “What am I gonna do? Buy a $200,000 car?” So we got Mark Abbott, the league’s lawyer. And Mark comes in and says, “Oh, you know, we can’t do that.” Finally he says, “OK, but that’s going to take some time.” Campos goes, “No, I’ve been down to the dealer this morning. They have it waiting for me. And it’s a red one.” Mark goes down there and the guy says, “This is the price. We don’t negotiate on price. But you’re such a nice guy, I’m going to throw the radio in for free.”

Jones: Jorge Campos. C’mon. He had a Ferrari. I got to see that one a few times. It was absolutely hilarious. A lot of the time it just sat there in the lot or in his apartment complex, but yep, I saw the Ferrari. He was craziest by far. He just didn’t care about anything, and he was having a good time doing it.

Kevin Stott (MLS referee, 1996-present; 2010 MLS Referee of the Year): Believe it or not, the match assignments were done by post and you had to actually check off a letter when you received it and send it back to U.S. Soccer by post. It was amazing. And then, once you got an assignment, you would find out which referee had the team the week before, and your job was to actually phone them because there was no email back then. The referees came up with that system themselves.

Travel

Pros in most sports leagues around the globe have a refined and private mode of travel to road games or preseason training. Think: extra leg room, premium food, complete and total discretion. Not so in 1996 for the first Major League Soccer franchises.

Agoos: It was no different than the last year I probably played in MLS [in 2005], which shows you the lack of progress in travel. We traveled commercially. I was always like last row, middle seat, kosher meal. But we traveled like everybody else, and we were a new league and so we all came to the airport with our Polos and people would ask us, “Hey, what do you do? What team are you with? What youth team are you with? Do you play basketball?” Nobody [in our squad] was probably over 6-foot-2.

Lalas: Economy-type stuff, middle seats, all that kind of stuff; explaining to people who you were, what a New England Revolution is. But I was from that generation where that’s what we did. We were spreading the gospel.

Jones: Like anyone else, middle back bathroom for you. There you go. That was it.

Meola: When I hear about guys fighting about charter flights now — which I think they deserve — I just chuckle to myself all the time, saying if any of these guys had any idea what was going on, they’d at least have some sympathy for the guys that played before them.

Lagerwey: Relative to waking up every morning and figuring out which park you’re going to practice at, the travel was like a luxury. Someone organized that; someone else bought those plane tickets. All you do is show up at the airport. Then you got in the 15-passenger van that every youth club uses now. That’s what MLS was at the time, and you throw everything in a van and you roll. And look, there was a certain sense of camaraderie. It has some elements of like minor league baseball to it, where everybody travels together, you do everything together, you go into the Olive Garden for meals, because that’s got a buffet. And life is simpler, because there just aren’t that many choices, economically.

Lalas: Did it at times get old and at times did you want to be recognized and respected for what you did? Yeah, but you have that little pity-party moment and then you move on and the fight continues.

Jones: I look at then compared to now and you got all these new collective bargaining agreements where they’re talking about mandatory chartered flights. Wow, that’s something special. It’s mandatory? Man, they’ve come a long way.

Agoos: Because all the other pro teams were traveling charter, at least I think most of them were, we would be sitting next to a mom and dad or a family. We were sitting next to loud kids. We would always have these flights that were either the earliest in the morning or the latest at night because they were the least expensive.

Day to day

In today’s MLS, the high-tech training facilities have become the rule rather than the exception. In 1996, clubs practiced in parks, fighting off teens throwing Frisbees, couples walking their dogs and kids playing games of their own.

Jones: Nobody in that group of former national team players wanted to play in Los Angeles because they thought soccer would not survive in L.A. I know of two, and I refuse to say the names, but I know specifically of two players that were offered that as they were doing the placement spots before me and they both turned it down, thinking that, “No, it’s not going to be successful.” But when it was my time up, I was like, “Yes, it’s my hometown. I want to be here.”

Lagerwey: We thought we had a gym we can use to change at [University of Missouri-Kansas City]. But when it rained, we couldn’t use the field. And they had a watering schedule too. And we couldn’t be on the field after the water schedule. So long story short, it wound up being like two days a week where we could actually use the field that we had a contract to rent. And the locker room was really impractical just because it was the athletic locker room. It was open, so we couldn’t leave stuff there; there’s no place to put gear. There was a period where we went to public parks to train; we would get a call in the morning and be like, “Meet at so-and-so park.” We literally put cones out and we would play in the park.

Lalas: We would go to play the LA Galaxy and we would train in the Rose Bowl parking lot because that’s where they trained, initially. It was crazy. The Rose Bowl parking lot is grass, so they said, “Well, there’s grass.” It got better in terms of a dedicated area later on for the Galaxy, but as far as the visiting team, I remember vividly going out and running around on what on any given Saturday was college football parking for the Rose Bowl. It was like going out to a park and then having training, which we also did too at different times.

Jones: As far as setup, we were [practicing] in the parking lot. Where we were training was an open field that we had to battle with people playing Frisbee, people with their dogs, kids having their own after-school sessions and all these things. We were clearing beer bottles and broken glass. It was part of the norm.

Lagerwey: Our athletes [in 2020] are literally monitored, even when they sleep. Everything that they eat, everything that they train, everything they do. I think in some ways, it’s a lot easier to succeed now because you just don’t have a lot of choices. But back then, you had to figure everything out on your own. And it definitely led to more creativity and less structure. I don’t think my offseason program was quite as diligent and rigorous as it might have been in the modern day. It probably made success a little bit more fleeting, but as my brother said at my wedding, I ate my way out of the league.

Vermes: The first year, for [New York/New Jersey MetroStars] home games, we used to stay at a hotel the night before the game. We used to stay at a special Holiday Inn, in New Jersey. Off to the side of the hotel, they had a two-story parking garage, and when we would stay there, they would put our cars there. We’d have to check in by a certain time, and they would put all of our cars in valet parking. Tab Ramos had just got to the team and he’d bought this new car, I think it was an Acura NSX, and I had this this green Honda Accord. And anyway, Tab and I were roommates and that night after dinner we decide to go for a walk.

I swear I can remember just like yesterday there was this van parked near the garage. You could just feel that there was something that wasn’t right about this van. And there are a couple guys in there and Tab and I were like, “Hey, let’s just walk through. Let’s get past this.” And we did. And so whatever, we just noticed it. We went for a walk and came back to hotel and went to sleep that night, woke up the next morning.

We come downstairs, we have breakfast, and now we’re going out to get our cars [before walk-throughs]. As we’re walking over, we had seen where our cars were the night before. I saw my car sort of moved from where it was the night before. Tab’s car wasn’t there. We just assumed that the valet probably grabbed this car and parked it somewhere so that we can get in and drive over to the field. And all of a sudden, we saw some cops, and next thing you know, they come over and tell us Tab’s car was stolen. They broke into my car too.

Remember when you used to stick your key into the lock on the outside? Well, they basically just plugged that thing right out. They broke into my car and broke the steering column — the only way they could turn my car on was with a screwdriver … I drove over in my car with a screwdriver pushed into my ignition to turn the car on and off. That was before our first home game!

Teammates

MLS had its fair share of stars in 1996, but the rank and file were made up of players making anywhere from $24,000 a year, a fraction of the kind of money Carlos Valderrama was earning — reportedly in the hundreds of thousands despite teams having a first-year salary cap of $1.13 million each — and players bonded over low-cost gatherings such as barbecuing and partying at one another’s homes. Without the built-out staffs of the league today, consisting of little more than the players, a few coaches, a trainer and a kit man, team’s sporting staffs were lean and conducive to building relationships.

Agoos: We used to have these weekly barbecues; the Argentinian players, guys like Mario Gori, for example, were absolutely incredible cooks. And they would grill everything, like, you know, hearts of pigs and snails. I mean, whatever it was that was moving, they would put on a grill and make it taste absolutely incredible. That was part of the bonding experience. And that was part of the reason why we continue to develop as a team. We were able to connect, and we were able to literally stand shoulder to shoulder with one another and die for the guy that was next to you, so to speak.

Lagerwey: [I spent] five years in the league and at no point did I have a goalkeeper coach, a nutritionist, a strength and conditioning coach or a performance coach. People forget, there were no general managers. There was a head coach and assistant coach, and then somebody that ran the business. Other than that, there was one trainer, and one kit guy and the players. It was absolutely as bare bones as conceivable. And then, of course, then you threw in Valderrama or Campos or [D.C. United midfielder, 1996-2003] Marco Etcheverry on top of that; just a random guy making a ton more money than everybody else.

Jones: Valderrama stands out, just as far as his ability to hold on to a ball in the center of the park was something special. But one that stands out for me was the Ecuadorian, Eduardo Hurtado. I think as far as shock values, obviously Valderrama holding on to the ball. But Hurtado, ask any of the players, like Eddie Pope, what it was like to try to run into him. He was like a brick house. He was so strong, it was ridiculous where he would bend over, stick out his rear and just bump people off. He was exceptional.

Lagerwey: We had fun. That was the ethos, man: You play a game and everybody go out together. Then if you had a day off, everybody gets together and then you have fun. You’d go to someone’s pool somewhere. There was one time, I think it was the Fourth of July, we all went over to [Predrag Radosavljevic, Kansas City Wizards midfielder, 1996-2000, 2002-05; Chivas USA manager, 2007-09; Toronto FC manager, 2010] Preki’s house and he had a volleyball court. We played volleyball all day. You organize these activities in places where it didn’t cost anything. That team did a lot of things together, and it felt more like a college team. The demographics of the league have changed so much.

Lalas: I remember weird things. When we used to play against the Columbus Crew in Ohio Stadium at the Horseshoe, never have I been in a locker room that had a better shower situation. It was like a cascading waterfall was dumped on you and it was straight overhead. They were probably completely illegal now in terms of water usage and all that kind of stuff. But I vividly remember being just mesmerized by the showers at the Horseshoe. These are the things that you remember: the strip clubs and the showers.

Vermes: I can’t remember if [the MetroStars] had 74 or 84 different players that season. Guys would come in, and they train with us for a week or two, and then somebody else will be gone. They’d sign this guy. Five guys would be brought in, four of them would just be released after a week. It was crazy, but you could do that on your roster because of how the contracts were back then.

This is funny, but it’s the truth. Back then, I think the date was you had to make it to July 1. If you made it to July 1 and you were still with the team, you’re guaranteed for the rest of the year. A guy here or there had a cell phone, but that was not the norm by any means. And so guys would not want to go home on July 1. They didn’t want to have to pick up the phone to have someone tell them that they were cutting them. You’d have guys who’d say, “Yeah, I’m not going home. No chance I’m picking up the phone.”

The infamous shootouts

If there was one element of Major League Soccer that set it apart — for better or worse — from every other league in the world, it was the shootout. Instead of a conventional soccer shootout — in which teams take five penalties from 12 yards out against a goalkeeper on the goal line, with the winning team decided by who converts more spot kicks — MLS in 1996 tried something with more energy. Players began with the ball 35 yards from goal and had five seconds to dribble toward the net — the goalkeeper also could advance off the line toward the player with the ball — before shooting. The winner was determined by the most successful shootouts on five attempts. The other element: These shootouts would decide regular-season games, as MLS did not have ties in year one.

Uniquely American, it was widely ridiculed in the game’s circles elsewhere in the world, but it created many fans in the U.S. and especially among many of those who participated.

Gulati: The thought was that Americans didn’t want to see games end in ties.

Agoos: I think it’s only loved by Americans, and those Americans probably don’t watch soccer, but I’ll say this: I loved it. I really love the concept because, number one, you have to have a bigger skill set to do it than to take a penalty. I took my cue from a lot of guys who were playing in the old NASL/Cosmos days: If you lift the ball up in the air, the goalkeeper would have to make a decision. If he comes out, it’s fairly easy to hit it over his head and you have an open goal; if he stays back on the line, you have a wider goal to shoot against.

Meola: I love them, I still think they should bring them back.

Jones: It was definitely out of the norm from anything that we had seen before. I think everybody knew that there was going to be some differences here and there to try to make it “exciting” for the American audience. I think we look back now and say maybe it was necessary at the beginning. But overall, for a true soccer/football traditionalist, I think it was a little bit of a jab in the side, just to see that in the end. But you know what? Look at all the stuff we have now and how much it has changed: Keepers not being able to pick up the ball when it’s passed back; VAR coming in; extra referees all over the place.

Lagerwey: I loved it. I was really good at it. I think if I didn’t have the best all-time record in shootouts, I bet I was real close. I have a career winning record as a result of those shootouts. I made my reputation in those shootouts.

Lalas: I thought that just from a philosophical standpoint, penalty kicks have always seemed to me such a completely separate and foreign type of way to decide a game. And so the shootout was something very strange and unique and new to soccer. I thought it actually did a good job of capturing what the necessities are as a soccer player in terms of dribbling with the ball, movement with the ball and then obviously scoring. And then from a goalkeeper, movement off the line. I thought it actually did a fair job of representing what the game was in that ultimate deciding moment. I didn’t have a problem with it.

Stillitano: The shootout was really loved by the foreign players, in particular. They all loved it; they felt it was more a measure of skill than nerves. As [New York Cosmos striker, 1976-83] Giorgio Chinaglia used to say to me, the goalie doesn’t save a penalty kick — you miss it. [The shootout] is a way to show skill. I was a purist. I didn’t like this shootout itself, but when I saw the reaction of the players and fans, I was OK with it. I really was.

Vermes: I liked it from the fans’ perspective in those early years, but I was glad to see it go. The two things I remember from that time was the shootout and the clock counting down. I mean, that was crazy. I’m glad those two things are gone.

MLS Cup

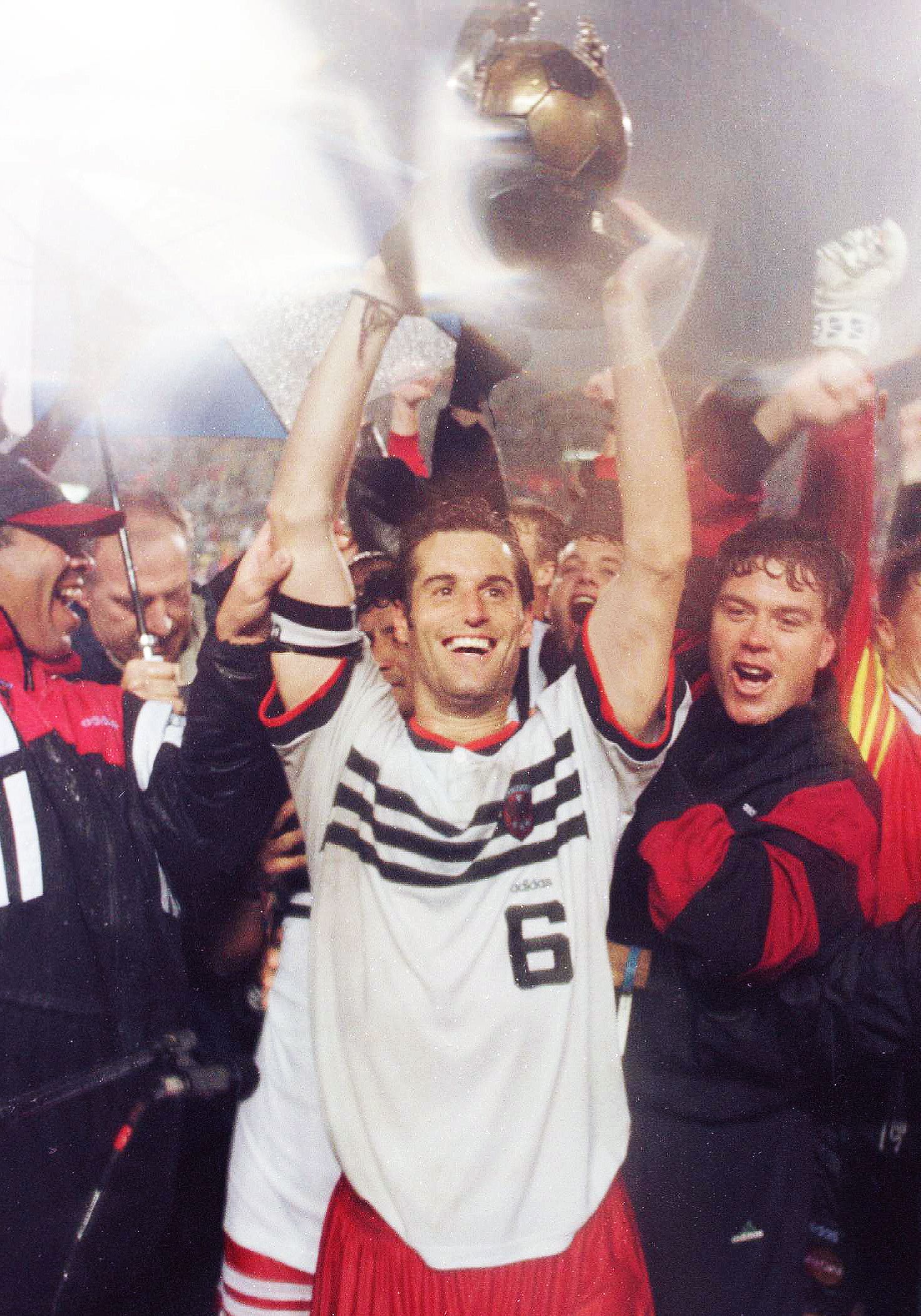

The inaugural MLS Cup was nationally televised and was contested between D.C. United of the Eastern Conference and LA Galaxy from the West. Played on Oct. 20 at New England Revolution’s Foxboro Stadium, heavy rain and gale-force winds would’ve meant a postponement in today’s climate; but on that day in 1996, with the pressure for the league to make a statement in front of a national audience, MLS Cup went on. (D.C. would win 3-2 in overtime, the winning goal scored by U.S. national team defender Eddie Pope.)

Agoos: I don’t know how many fans we had, but 15,000 to 20,000 fans just braving wind and gales and rain. The rain was going sideways. I mean, I don’t think that that game could have been played or should have been played given the field conditions. But I don’t think there was a choice, and to not play the first year, the inaugural year with the inaugural final, I think was just not an option. And we did wind up playing. It was incredibly cold, incredibly windy, hard to play on the ground because of the conditions and really the way the puddles were aggregating were in the penalty areas, the most important part of the field. I remember Cobi Jones dribbling the ball into the penalty area, almost going one-on-one with the goalkeeper and just completely running past the ball.

Williams: In reality, the game should’ve never been played because of the conditions. I mean, literally, you would step in the water and it would be up to your ankle.

Gulati: The game’s over, I think I’m down on the field, and they were doing the tallies of the MVP of the game. I’m listening on the radio, they’re asking who the MVP is but we don’t have the tallies yet. And so I just basically said into the microphone on a headset, it’s Marco Etcheverry. Etcheverry’s the MVP. So basically, I picked the MVP, except I didn’t realize at the time that there were media also [listening in]; it was like playing in the press box that I just picked the MVP rather than the media picking the MVP, and I was doing it just because, you know, we ran out of time, not because I really wanted to pick. But it kind of furthered the, you know, MLS “More or Less Sunil” nonsense.

Would you do it again?

Was it worth it? With the league in its 25th season, it’s hard to come to any other conclusion beyond a resounding “yes,” and that’s a nearly unanimous consensus among our respondents.

Agoos: Compared to today, it was probably semi-pro at best. And that’s a good thing, and that shows progress of where we are today as a league. The first year, it was literally just getting this league off the ground. And it was something that we all supported: players and coaches, administrators, league officials. It was a dream of ours to have our own league. If we had to do with less than the highest-level conditions that we’re experiencing now or they’re happening in Europe, fine. We would deal with those to make sure that there was history and a legacy for this league to continue.

Gulati: In some ways, the first year was terrific. We started off well, with big crowds. Sellout in the first game, then L.A. and New York with big crowds. And people were excited. We had lots of goals and all of that. The second year was always going to be harder, and it didn’t live up to what the first year had been. Certainly, you know, the newness of MLS gave us some breathing room, both with our sponsors, with Univision, in particular. Between signing Campos earlier, and Anheuser-Busch and Budweiser were big sponsors and so on. But you couldn’t survive on the newness.

Lagerwey: It was amazing, man. I know a lot of guys who were better players than me that fell somewhere before me who didn’t get that opportunity. They had to go abroad and play in the third division in Czechoslovakia or Yugoslavia even to get a chance. Look, it was a good life. I might have had an apartment with no air conditioning, in what’s called an “up-and-coming area of Kansas City.” I drove a 1990 Toyota Corolla. You definitely didn’t want to upgrade from that because otherwise it was definitely getting stolen. We had a lot of fun. It wasn’t the serious endeavor that it is now.

Lalas: It was very different, but I always guarded against complaining or whining unless it was really necessary. Because I recognized that this was going to be a work in progress for a long time, and I wanted to be part of something from the start. And if you’re there from the start, you’re going to go through all of the ups and downs and the trials and tribulations and challenges, both on and off the field. And we did it.

Stillitano: I used to say this in the best way: The only thing major league was our title.

Meola: For guys in my generation, we didn’t have a league to aspire for. We were hoping and praying, but we didn’t have anything to look up to like kids do now. And it’s a whole different ballgame now. I don’t know if you ask the percentage of fans currently in MLS, with expansion and with everything going on, the percentage has to be really low of people that support the game right now that didn’t have a league to support growing up.

Jones: No one was thinking that this was gonna last. Soccer was still considered the “redheaded stepchild.”

Stott: Looking back on it, the non-televised games did feel like they were happening in a vacuum; but if you were to ask us back in ’96, we would say this is it. This is the moment, and nothing else is happening outside in this city except for this.

Lalas: However bad I or others frame it or make it out to be, it was never that bad. And to be quite honest with you, we were still living that dream. And we were doing something from scratch. And so there was a pride associated with it, even in challenging situations. But those challenging situations are relative, because 99.9% of the people would have killed or died to be able to have that opportunity and we reminded ourselves about that.