Products You May Like

The advent of the Video Assistant Referee (VAR) in the Premier League hasn’t gone smoothly since its introduction in 2019.

Its introduction into English football was delayed, with the Premier League being the last of the “Big Five” leagues in Europe to adopt it. The Bundesliga and Serie A were early adopters in 2017-18, but the Premier League hesitated for two years before voting to use it from the 2019-20 season.

– VAR’s wildest moments: Alisson’s two red cards in one game

– How VAR has affected every Premier League club

– VAR in the Premier League: Ultimate guide

High-profile errors and protocol missteps have dogged Professional Game Match Officials Limited (PGMOL), the body that oversees refereeing, ultimately resulting in the Premier League being the only “Big Five” league not to have a single referee selected by FIFA to act as a VAR at the World Cup later this year.

After 1,140 games overseen from the VAR hub at Stockley Park, trends have started to emerge which show the influence of VAR both on the game itself and its Laws.

Here, we take a look at what we’ve learned so far.

VAR now brings more goals than it disallows

It might be hard to believe, but it’s true. This season was the first that saw fewer goals disallowed by VAR than it produced.

Indeed, that first season of VAR in the Premier League in 2019-20 was a massive culture shock to fans, players and pundits. The Utopian idea of a fairer league was replaced by a sense of injustice, with the VAR taking away what made the game special — goals and the spontaneous nature of celebrations. Only 27 goals were added by VAR decisions, with 56 ruled out; a huge net loss of 29 goals across the 38-week season.

But things are improving, even if it doesn’t seem that way on a week-to-week basis. The laws are adjusting, offside is being tweaked and the game is learning. It’s going to take a lot longer to get right, and there are far too many imperfections around things like subjective penalty decisions.

In 2020-21, that net loss improved to eight goals, with 42 goals ruled out and 34 allowed.

And in the season just gone, the turnaround was complete, with VAR actually creating four goals: 47 added and 43 disallowed.

Of course, it’s not a simple as goals alone, but at least the system is now a net benefit on this metric rather than a marked negative.

But is VAR getting less involved?

Use of VAR remains pretty static across the seasons, at an intervention every 0.32 games — or one every three games. That’s pretty much standard across all the top European leagues.

Over the last two seasons, the number of overturns in the Premier League is almost exactly the same, with 123 in 2020-21 and 120 in 2021-22 — slightly higher than the first season of VAR in 2019-20, which had 109 overturns.

How VAR and the handball law have learned to co-exist

It was a complete mess which took the International Football Association Board (IFAB), football’s lawmakers, three attempts to get right. But we now appear to have got there — at least with accidental attacking handball.

In 2014, the IFAB created its football and technical advisory panels to shape the Laws of the Game. Contrary to popular belief, these panels include many high-profile former players and coaches — such as Arsene Wenger, Luis Figo, Hidetoshi Nakata, Daniel Amokachi and Zvonimir Boban. One of the very first tasks was to redefine the handball law. It was a long process which took several years, beginning before the introduction of VAR. We would soon find out how incompatible the two processes were.

While many think the handball law was changed for VAR, it was in fact the opposite — it was changed without considering the implications of VAR. The forensic analysis of identifying handball offences in both attacking and defensive situations led to goals being disallowed and penalties awarded which in ordinary play would never be penalised.

For instance, the accidental handball law was officially added to the laws in 2019, preventing any goal from being scored if the ball hit the hand in the attacking phase. But the IFAB was forced to reword it twice in the successive summers that followed after a raft of controversial decisions across the leagues.

In the 2019-20 season, 15 goals were disallowed for handball through VAR in the Premier League — though the law had actually been enforced far more strictly in the European leagues and UEFA competition.

There were several high-profile incidents early on, including Aymeric Laporte‘s late “winner” for Manchester City against Tottenham Hotspur ruled out for handball. Even though the ball only brushed the arm of Laporte and the decision caused controversy, the IFAB would later use this in its video presentation of how the law should be correctly applied.

When the IFAB changed the law for 2020-21, so that it only applied to the scorer and the player who created the goal, the number of goals disallowed by the VAR dropped from 15 to six.

And in the summer of 2021, the law was modified once more to the goal scorer only, and only three goals were ruled out.

It’s a classic case of unintended consequences once the scrutiny of the VAR comes into play. It has been seen in other IFAB law changes too, such as a goalkeeper encroaching off the line on a penalty which led to a rapid backtrack at the 2019 Women’s World Cup just weeks after it came into law.

VAR’s growing influence on penalties

Have referees stopped making decisions, and instead rely on the VAR as a safety net? It’s not something you can truly assess, though last season’s stats indicate there is a trend developing with a higher percentage of spot kicks being awarded through VAR.

Penalties awarded through VAR have increased season-on-season: 22, 29 and then 38 this season just gone.

In each of the first two seasons, around 23% of all penalties needed the advice of the VAR. But last season, this increased markedly to 36.89% (38 out of 103 penalties awarded).

A major influence on this has been handball. Unlike with accidental attacking handball, offences are increasing — and the majority come from the forensic analysis of VAR.

In 2019-20, the Premier League saw 20 penalties for handball, with seven of those coming via VAR review (35%). By 2020-21 the number of penalties was similar: 21, with 12 from VAR (57.14%). And last season we saw 25 handball spot kicks, with another increase to 15 from the video official (60%).

While the IFAB did revise the wording of defensive handball last summer, this was more a streamlining of the terminology as the interpretation remains largely the same — so the frequency of penalties remains high.

How the Premier League reduced total penalties

If ever there was an indicator for soft penalties, it’s the huge number of overturned spot kicks in 2020-21. The VAR cancelled 22 that season, compared to just seven in 2019-20 and nine last season.

Even with those 22 overturns, 2020-21 still saw a record number of penalties with 125 awarded over the 380 games. Even bigger increases had been experienced across the major leagues that season — up 100% in France, 50% in Germany and 37.5% in England. Italy had suffered its peak in 2019-20, when an incredible 186 penalties were given (it was still 141 in 2020-21.)

After the success of lighter-touch refereeing at Euro 2020, the leagues agreed to try and implement a similar philosophy. The goal was to reduce the number of “soft penalties,” to ensure that contact from defender on attacker was a foul.

This certainly worked, but not without controversy in some cases. Judging the consequence of contact is always difficult from a VAR hub miles away, so there were occasions when many felt the VAR should have intervened after contact but didn’t. For instance, Diogo Jota‘s claim for a penalty in Liverpool‘s draw at Tottenham.

The numbers do show the success of the overarching policy, however. After those 125 penalties were awarded in 2020-21, this fell to 103 last season, with VAR spot kicks increasing by nine season-on-season.

Has VAR offside improved?

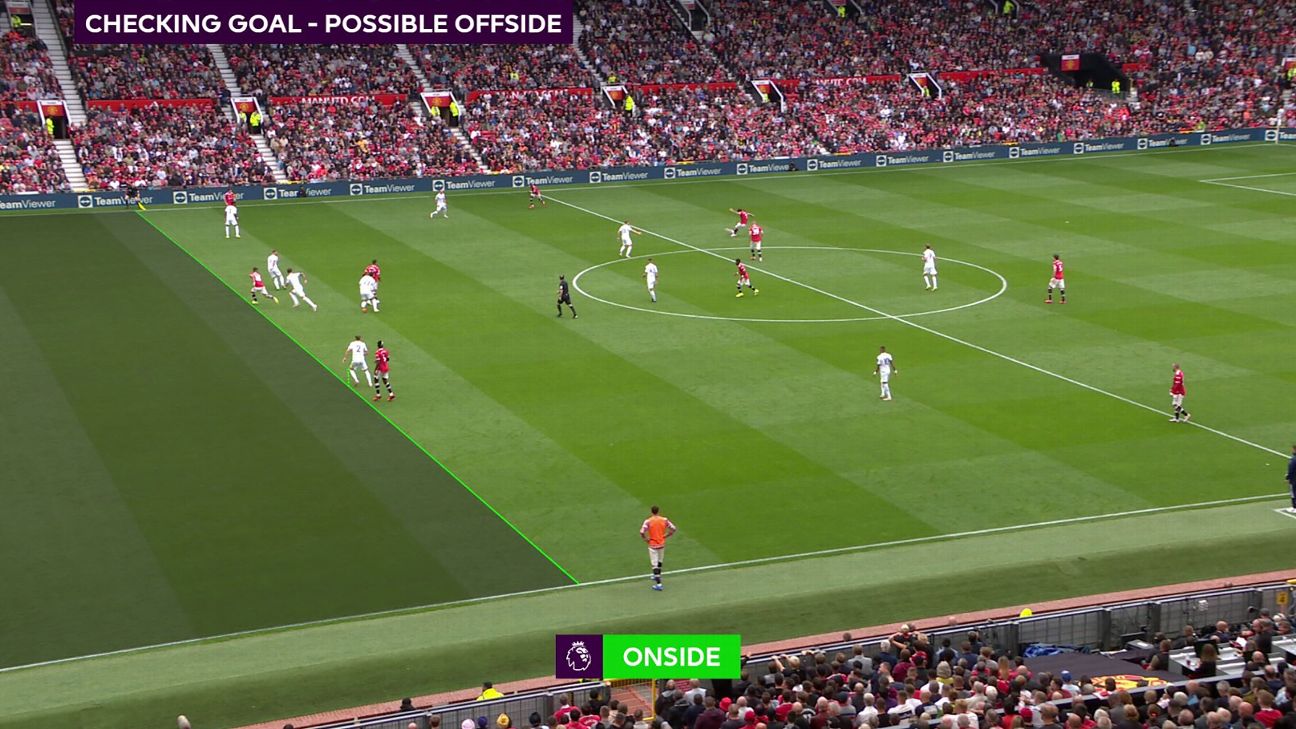

Last summer, the “Big Five” leagues all followed UEFA’s lead by adding a tolerance level to VAR offside, so that if the lines you see on television are touching then the player will automatically be ruled onside.

Manchester United‘s Bruno Fernandes was the first player to benefit from the new tolerance level, as his goal against Leeds United in August would have been disallowed under the old interpretation.

PGMOL said that if applied to the 2020-21 season it would have added 20 goals. That campaign, 32 goals were disallowed via VAR — though not all 20 would come out of that total because of goals actually disallowed by the assistant and confirmed by the VAR.

And in the season just gone, there was no change, with 32 once more ruled out for offside. Of course, on a factual decision such as offside, much rests of the decision of the assistant, and it could purely mean this season they made a few more mistakes. But the number of goals allowed rose from seven to 11 — the best campaign in terms of reclaimed offside goals.

The offside stats are inflated by another of the IFAB’s changes to handball, meaning the outside of the arm rather than the armpit is used for offside. It edges attacking players further forward as they lean into a run, and has caused more goals to be ruled out via VAR.

We’ll get a taste of the future at the World Cup in Qatar in November, when FIFA rolls out semi-automated offside in all its glory. It means almost all offside decisions could be made within seconds, which will transform the fan experience. The domestic leagues will have to wait until 2023-24 to get this new technology, so another season of line-drawing awaits.

– Semi-automated VAR offside has arrived; here’s how it works

Once fully implemented, it could eliminate many instances of the “delayed flag,” as the VAR will be able to confirm with the assistant whether a player is offside. And it will also remove the interminable wait for an offside decision when a goal has been scored.

Why VAR could never really be like it was at Euro 2020

At the start of this season, PGMOL boss Mike Riley said he wanted VAR to be like it was at Euro 2020 by “raising the threshold.” You could achieve this by refereeing in a more lenient manner, which is shown by the drop in penalty kicks. But if you raise the bar on VAR too in domestic leagues, it doesn’t necessarily follow that decision-making in general will improve.

Indeed, contrary to the popular narrative, VAR was used slightly more at the Euros last year than it has been in the Premier League for the past two seasons, averaging 0.35 overturns a game compared to 0.32.

But tournament football is very different, with one key match incident a game compared to three in the domestic leagues. UEFA competitions also have only the very best referees from around the continent, less prone to making errors. In all regards, it’s a situation no domestic league could ever hope to replicate.

The Euros also had 51 matches, equal to just five rounds of the Premier League. While you can certainly take learnings from the way games have been officiated, making assumptions about VAR based upon a small sample size always seemed problematic.

And that leads us to a key area where the Premier League must change.

What’s the point of the pitchside monitor?

At Euro 2020, not a single VAR review was rejected by the referee at the monitor. Last season in the Premier League, not a single VAR review was rejected by the referee at the monitor. Coincidence? Despite the small sample size at the Euros, it seems a logical connection.

In the first half of 2019-20, monitors were at Premier League grounds but they were not used at all. That changed in January when PGMOL bowed to pressure and agreed to use them for red cards only. By the IFAB’s AGM in February 2020, the Premier League had been ordered to follow protocol and use the monitor for all subjective decisions.

This had a clear impact as on five occasions in 2020-21, the referees stuck with their own decision when visiting the screen.

But this season just gone, the Premier League has regressed. While the referees have visited the pitchside monitor for all subjective overturns, not once have they rejected the review. PGMOL insists that the referees retain all options, but it’s hard to comprehend that in around 65 pitchside reviews they haven’t once disagreed with the VAR.

So, why is this? It comes down to the “high threshold” for interventions. If the bar is theoretically placed high, the logic is that the VAR will only send the referee to the monitor if it’s an error beyond any doubt whatsoever.

Problem? This assumes that the VAR won’t make a mistake, that they will never mistakenly back the referee’s original call. It removes the VAR’s own subjectivity, too, and is a key reason for errors such as the penalty that wasn’t given for handball against Manchester City midfielder Rodri at Everton, which led to an apology from Riley.

The nature of VAR, identifying “clear and obvious” errors, does mean a referee turning down a review should be rare. After all, the monitor isn’t there to “have another look,” but to overturn a decision.

Review rejection is still low across other leagues, but not to have a single one across a whole season suggests referees are being encouraged to go with the VAR advice, rather than their own opinion.

So why even bother with the monitor? Even if referees are simply confirming the overturn it remains a crucial tool for game management, for officials to be able to explain to players exactly why a decision has been changed.

An excellent example of this came in the FA Cup tie between Manchester United and Aston Villa, when Jacob Ramsey was ruled offside for impeding Edinson Cavani from an offside position, leading to Danny Ings‘ goal being disallowed. By viewing the incident, referee Michael Oliver was able to explain to both captains why the goal was being disallowed. Without the monitor, there wouldn’t be this clarity and it could impact the referee’s authority.

“Clear and obvious” still isn’t clear and obvious

If there’s one phrase that supporters dislike more than any other, it’s “clear and obvious” for changing a referee’s decision.

The problem is “clear and obvious” doesn’t really mean anything, because the over-riding factor will always be the decision the referee has made. It means two identical situations in the same game can result in different outcomes based upon the referee’s original decision — because, for instance, to give a penalty or not can both be subjectively correct.

It means calls for greater consistency in decision-making through VAR is impossible — because it’s the decision on the pitch which is always the marker.

It’s where VAR will always struggle. While there are some decisions which are obvious mistakes and should be changed, the majority fall into the middle ground of subjectivity, where a case can be made either way. There will always be one set of fans who feel aggrieved, who believe VAR hasn’t worked for them.

As a result of this, there’s no real fix for “clear and obvious.” Unlike in other sports, the vast majority of decisions in soccer are subjective, and you wouldn’t get universal agreement even among qualified referees. But that’s also why “clear and obvious” has to exist. If the VAR is making all the big calls, then they are refereeing the game to their own subjectivity and the match referee on the pitch is no longer in control of the game.

Information provided by the Premier League and PGMOL was used in this story.