Products You May Like

Possession is an extremely common topic in soccer discussion. It’s almost a written arrangement: The best (and richest) teams in Europe — think Manchester City, for one — will dominate the ball and take it back the moment they lose it, while the lesser (and/or less monied) teams will have to make do without it.

In this, the age of Pep Guardiola, having the ball is tantamount to winning. If you know who had more of the ball over the course of a given season, you probably know who ended up with more of the points.

Points per game for teams with different possession rates in Europe’s Big 5 leagues (2017-18 to present):

Hog the ball, win trophies. Sounds downright orderly, yeah? But if you’ve ever actually watched a soccer match — and if you’re reading this, odds are good that you have — you know that “orderly” isn’t a very accurate way to describe the sport. For every long string of passes, there’s a string of ineffective headers or a quick, long pass that goes awry.

For every run of order, there’s a run of chaos.

– ESPN+ viewers’ guide: LaLiga, Bundesliga, MLS, FA Cup, more

– Stream ESPN FC Daily on ESPN+ (U.S. only)

– Don’t have ESPN? Get instant access

Look, for instance, at the poster child for both dominance and ball dominance: 2017-18 Manchester City. This Guardiola-n ideal of a squad enjoyed 71% possession, the highest of any Big 5 team in the last five seasons, and posted 100 points, the most in the history of the Premier League. They hogged the ball like few could ever dream, but only 48% of their possessions lasted more than 20 seconds, and 38% lasted under 10. Even the most organized City team on record was playing about half of a given match under reasonably chaotic circumstances.

A healthy percentage of any match between any teams is spent in transition between attack and defense (or vice versa). Proper transition play isn’t an equalizer, exactly. It can’t make a bad team good, but it is the polish that can make a good team great. It can decide title races and relegation battles, too.

For the purposes of exploration, let’s talk about a specific type of transition

Let’s talk about the quick-burst possessions that occupy a solid portion of a given match: possessions that begin outside of the attacking third and last 20 or fewer seconds. These account for over 60% of the possessions in a given match, and most of them go absolutely nowhere.

Whereas teams average about 0.13 shots per possession overall, these possessions — we’ll keep it simple and call them “transition possessions” for this story — average just 0.05. Still, these possessions have accounted for 29% of all goals in Big 5 leagues over the past five seasons; they are specialized situations that can have more impact than set pieces (20% of all goals).

Great transition teams can average nearly a goal per match from these possessions. In fact, this season’s Bayern Munich team is currently averaging 1.1. Julian Nagelsmann’s squad has scored 18 goals from such possessions in 2021-22 and allowed just four: they might be the best and most persistent transition team since Nagelsmann’s RB Leipzig scored 33 such goals in league play in 2019-20 and allowed just eight. They are dominant in all phases of the game, but prolific transitions have helped them stake a nine-point Bundesliga lead at the midway point of the season.

Data from these transition possessions ends up being one part quality, one part philosophy. As you might expect, rich and athletic teams like Bayern and PSG (before 2020-21, anyway) have generally been the best at combining transition scoring opportunities while limiting opponents’ chances. But for everyone else, it’s a tactical card to play.

Take, for instance, Mainz and Wolves.

Mainz have generated 24 points in 17 matches (1.41 per match), good for ninth place in the Bundesliga and four points from the top four. Their matches are chaotic and exciting, featuring 1.35 combined goals per match from transition possessions — 0.71 for Mainz, 0.65 for opponents.

Wolves, meanwhile, have pulled 25 points from 18 matches (1.39 per match). They’re eighth in the Premier League, three points from the top five. They have been the anti-Mainz: They’ve yet to score a transition goal this season, and they’ve allowed only one. These clubs have produced nearly identical results with approaches that couldn’t be more different.

Another example: Napoli and Atalanta.

Napoli has 39 points in Serie A play, Atalanta 38. Napoli’s possession rate is 58%, highest in the league, while Atalanta’s is 56%, fourth-highest. But Napoli matches have featured just five combined transition goals this season (three for, two against), while Atalanta matches have featured 25 (16 for, nine against). Statistics from these transition moments belie your manager’s philosophy more than possession rate or perhaps anything else in the analytics arsenal.

What can these transition stats tell us about the 2021-22 season?

To date, across Europe’s Big 5 leagues, 17 teams have a goal differential of +5 or higher in these transition possessions.

-

+14: Bayern Munich (18 scored, four allowed)

-

+10: Real Madrid (15-5), Inter Milan (14-4), Montpellier (13-3)

-

+8: Sevilla (8-0)

-

+7: Atalanta (16-9), Bayer Leverkusen (14-7), Leicester City (12-5), Liverpool (12-5)

-

+6: Rennes (10-4), Manchester City (8-2)

-

+5: Atletico Madrid (12-7), Real Betis (12-7), Marseille (9-4), Chelsea (8-3), West Ham United (8-3), Nice (6-1)

Four of five current league leaders are accounted for among this group while the fifth, France‘s PSG, sit at +1 (8-7). Only one team across the leagues has managed to average 1.7 points per game or more with a negative goal differential in transition possessions: Freiburg, with 29 points and a minus-3 differential.

Predictably, the teams with the worst goal differentials in these possessions are primarily the worst teams in these leagues. Fifteen teams have a goal differential of -5 or worse:

The most interesting names on this list: Leeds and Lazio.

Leeds were +5 in this department last season, scoring 21 and allowing 16. This season, they’re on pace to score about half those transition goals while allowing twice as many. They are attempting more shots per transition possession this season, but their shot quality is dreadful. They have been unlucky to allow 14 goals from just 8.4 xG in these transition possessions, but a 2020-21 advantage has turned into a rather drastic disadvantage in 2021-22. Only Metz and Stuttgart have seen their per-game goal differential from transition possessions flip more from last season.

Lazio, meanwhile, remain a decent team — good enough to advance to the Europa League knockout rounds and take seven points from league matches against Roma, Inter and Atalanta. But they’ve allowed 11 transition goals across eight matches, from which they managed only two wins, two draws and four losses. It’s cost them dearly, and they’re eight points back of a top-four spot heading into the holiday season.

Here are some other transition-related storylines from across the Big 5.

PSG has completely hit the brakes

0:48

Gab Marcotti and Julien Laurens discuss Sergio Ramos’ red card for PSG against Lorient.

Mauricio Pochettino has never been big into aggressive transitions. Even in his possession-friendly days at Tottenham Hotspur — 62% possession in 2017-18 and 59% in 2018-19 — Spurs scored on only 1.1% of transition possessions (above average, but not elite) while allowing goals on only 0.5% of transitions.

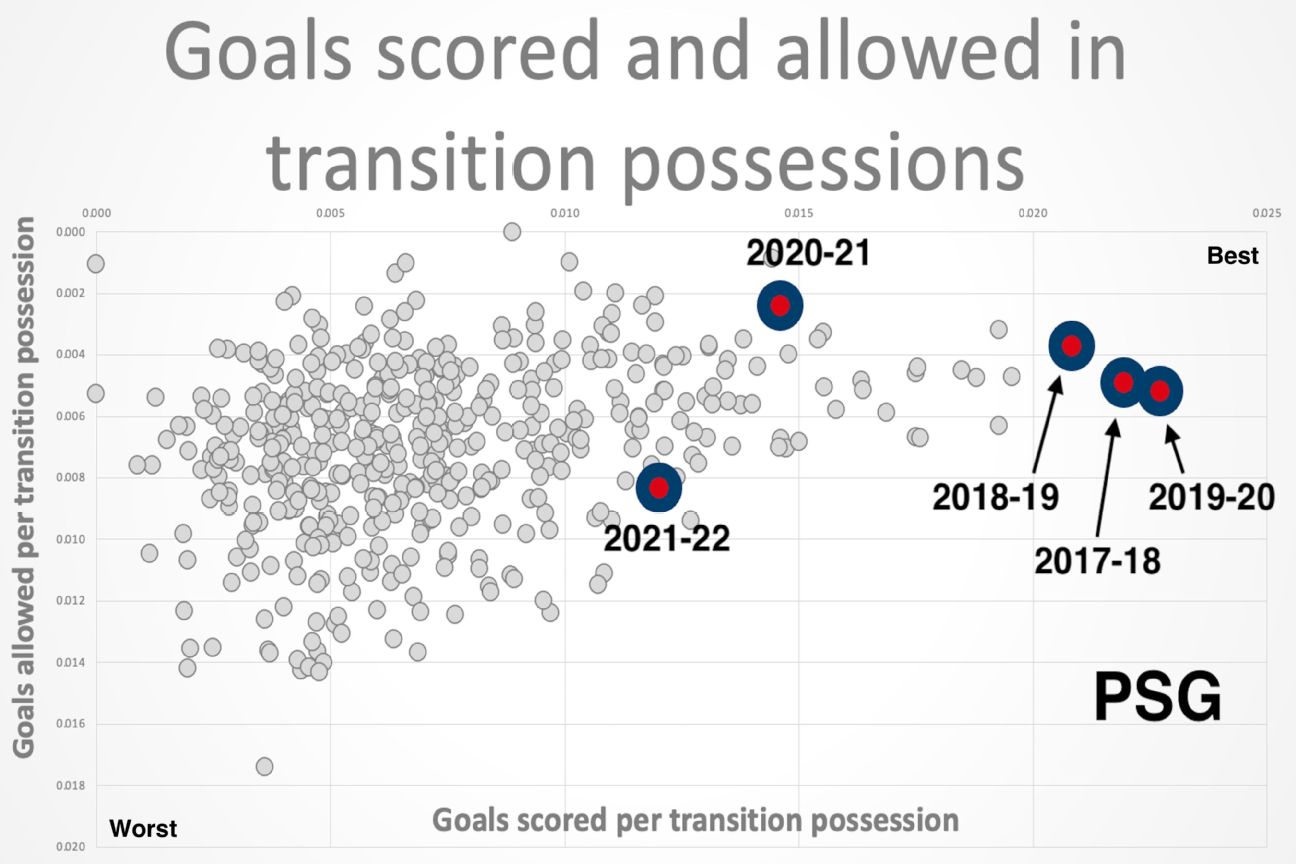

Since taking over at PSG last year, his tendencies, plus an aging core of attackers, have changed how a once-dominant transition team plays.

Data via StatsPerform

Under Unai Emery and Thomas Tuchel, PSG were the most devastating transition team on record. They scored on 2.2%, 2.1% and 2.3% of transition possessions, respectively, from 2017-18 through 2019-20, but that fell to 1.5% last season (the second half of which was with Pochettino in charge), and they’re at 1.2% this season.

Not surprisingly, Kylian Mbappe has been the transition king for PSG. In the three seasons from 2017-18 to 2019-20, he scored 35 goals with 13 assists in these transition possessions, equivalent to 0.73 goals and assists per 90 minutes. In the season and a half since, he’s scored 12 with four assists (0.37 goals and assists per 90).

The transition contributions of Neymar and Angel Di Maria have fallen off a cliff. The two combined for 22 goals and 26 assists in transition possessions from 2017-18 to 2019-20; they have two transition goals and seven assists since. Meanwhile, PSG is worse at stopping transitions than at any point in recent history: They’re allowing goals on 0.8% of transition possessions, slightly more than the average among teams in the Big 5.

None of this is stopping PSG from romping toward a Ligue 1 title, of course — they’re 13 points up on the field at the moment — but it’s rendered them a bit more stolid and one-dimensional, reliant on the unique and brilliant skills of their attackers to break down defenses. When you’ve got that much attacking skill, it can work out for you, but their overall level of play is such that, after they reached the Champions League finals in 2020 and the semis in 2021, FiveThirtyEight projects them as the ninth-favorite to win the Champions League this season.

Tired, old Real Madrid might be the most dangerous transition team in Europe

1:04

Craig Burley breaks down everything that has gone right so far for Real Madrid and how they can easily take home the LaLiga title.

Granted, part of the reason PSG only has a 44% chance of making the quarters in the Champions League is because of who they drew in the first knockout round: Carlo Ancelotti’s Real Madrid. Since October’s international break, Los Blancos haven’t lost: they’ve won eight matches with two draws in league play (a run that includes wins over Atletico Madrid, Barcelona and second-place Sevilla), and they swept their last four Champions League matches.

As I wrote for a Madrid Derby preview earlier in December, “Ancelotti has lowered the defensive intensity a bit, and he has slowed the tempo to a crawl. … This can backfire at times, as limiting possessions when you’re likely to have a per-possession advantage can simply result in you creating fewer total advantages. But it’s working for this group, and it’s keeping a few miles off of old legs, especially with the work [David] Alaba and younger guys are doing in ball advancement.”

Ancelotti has indeed kept the tempo low for the most part, which translates to fewer transition possessions than pedal-to-the-metal teams like Bayern or Liverpool. But when they spring forward in transition, often via turnovers in midfield, it tends to go really well.

Real Madrid has scored on 2.0% of its transition possessions this season, most of anyone in the Big 5, and their 14 transition goals are more than everyone else’s but Bayern (18) and Atalanta (16). The dynamite duo of forward Karim Benzema and winger Vinicius Junior has combined for nine transition goals and four assists, and two of the assists have gone to one another. Benzema sprang Vini for a breakaway and a game-winner against Celta Vigo in September, and Vini teed up a gorgeous Benzema goal in transition to go ahead of Atletico in the Madrid Derby.

Only one team is within 12 points of Real Madrid in the LaLiga race right now: Sevilla, which has taken a completely different approach to contention.

Julen Lopetegui’s squad is the only Big 5 team not to have allowed a goal from a transition possession to date. Only five Big 5 teams allow fewer shots per transition possession, and only six allow a lower xG-per-shot average. Granted, they’ve only scored a slightly above-average eight transition goals, but they snuff out transitions better than anyone in Europe, and it’s helped them to stay within eight points of the leaders with a game in hand.

Transitions contributed to Ole Gunnar Solskjaer’s demise at Manchester United

1:59

Football agent Giovanni Branchini explains on Gab & Juls Meets why he suggested to Cristiano Ronaldo’s agent that he should sign for Manchester United.

The Premier League is one of stylistic variety. The best teams (Manchester City, Liverpool and Chelsea) are as good as anyone in these transition moments, sure, but beyond the elites, you’ll actually find a wide array of philosophies.

You’ve got teams like Arsenal, Wolves and Brighton seeing different levels of success with particularly languid transition approaches. You’ve got West Ham United threatening to snare a Champions League bid with a unique combination of counterattacking, transition defense and set-piece domination. You’ve got Watford and Leeds United keeping things pretty wide open (with mixed or downright poor results). You’ve got Jamie Vardy still doing devastating things in open spaces — he’s got four goals from transition possessions, paving the way for Leicester City to lead the league in the category.

You’ve also got a data point that hints at where things went wrong for Ole Gunnar Solskjaer and Manchester United this season.

In 2019-20 and 2020-21, Solskjaer’s two full seasons in charge at Old Trafford, United allowed an average of seven goals per season from transition possessions. They were above average in scoring on 1.2% of their transition possessions in both seasons, but they were particularly good at limiting opponents’ opportunities.

In 2021-22, things fell apart in this regard. When Solskjaer was fired on Nov. 21, United had already allowed seven such goals this season, including four in losses and one in a draw against Everton. They had scored eight such goals of their own (only one combined from star signings Cristiano Ronaldo and Jadon Sancho), giving them a +1 goal differential in transition possessions. They were +15 and +17, respectively, in the previous two seasons. They’re +2 since the firing, with goals from both Sancho in a draw against Chelsea and Ronaldo in a one-goal win over Arsenal.

Andrea Pirlo, transitions master

Whatever issues Pirlo had in his first and only season as Juventus manager in 2020-21, “transition” wasn’t among them. Juve saw its nine-year league title streak end on his watch, with Inter posting 91 points and winning the Scudetto by 12, and Pirlo was dismissed. But despite a youth movement (particularly in midfield), Juve were still only a point out of second place, in part because of excellent transition play. They led the Big 5 with a +19 goal differential in transition possessions in 2020-21, scoring 27 and allowing only eight. Cristiano Ronaldo scored 10 transition goals, while Alvaro Morata and Federico Chiesa combined for nine goals and nine assists.

This season, with Max Allegri back in charge, Juve’s deficiencies remain, but the transition prowess has disappeared. They’re on pace to score only 14 transition goals and allow 10. Ronaldo’s gone, and Morata and Chiesa have combined for two transition goals and no assists. Allegri has turned back the clock a bit from Pirlo’s attempt at a modern, possession-based system, and while things have begun to look up for the Bianconeri — they’ve taken 13 points from their last five matches — they remain four points outside the top four.

Despite Ronaldo’s lack of pressing, Pirlo was able to create a possession-heavy, transition-friendly squad, one that has gotten worse since his departure. He has been linked to a number of lower-level managerial jobs of late, but you could make a decent case that he should still have his previous job.